Heads or Numbers

What does the population identify with? Especially when it comes to money? Initially, coins always showed a god or goddess, or a ruler. In the last 200 years, however, they have always shown a number. Have you ever wondered why? We seem to trust the number more than the person. Heads or tails shows how people feel about money as a medium of exchange. The change from heads to tails (or number) had profound consequences.

Head: a person, a personality, focus on who or what

Number: the pure exchange function, focus on how much

Athena: Trust in the Goddess

Athens. Tetradrachmon, c. 450 B.C. Head of goddess Athena with helmet, on helmet cup palmette and three decorating leaves from olive tree. Back: Owl sitting, behind branch from olive tree with leaves and fruit and crescent moon.

Athens. Tetradrachmon, c. 450 B.C. Head of goddess Athena with helmet, on helmet cup palmette and three decorating leaves from olive tree. Back: Owl sitting, behind branch from olive tree with leaves and fruit and crescent moon.

The relationship between the city and the patron deity was understood at that time as a kind of contract, in which the deity was obliged to provide its assistance only as long as it received the worship due to it from the citizens entrusted to its care.

Whether it was Athenian aid or silver found in the Attic mines near Laurion, or the uncompromising power politics of Athenian democracy, the owls, as the city's coinage was called in antiquity, were the most important trading currency in the entire Mediterranean region in the late 5th and early 4th centuries BC.

Alexander the Great: depicted as a god

Alexander III, king of the Macedonians (336-323 BC). Drachma, 333-323 BC Head of Heracles with lion scalp.

Alexander III, king of the Macedonians (336-323 BC). Drachma, 333-323 BC Head of Heracles with lion scalp.

When Alexander, later to be called the Great, set out to conquer the Persian Empire, the 70 talents of silver in his treasury were offset by 200 talents of debt. He had used this money to procure supplies for his army. 30 days they would last, a short period of time to conquer a world empire! Alexander was doomed to success. And indeed, his victory at Granikos in May 334 BC provided him with the means to finance his campaign from then on with the help of the booty.

This first victory gave Alexander access to the rich cities of Asia Minor, previously controlled by the Persians. After the conquest of Sardeis and Tarsos in 333 BC, it is likely that Alexander introduced his own image for his silver coins, initiating a coinage that eclipsed anything that had come before. For the obverse, he chose Heracles, the progenitor of his dynasty, who was considered the champion of good against evil and was personally revered by Alexander.

Julius Caesar: "I rule"

Roman Republic. Denarius minted under the supervision of the Master of the Mint P. Sepullius Macer, 44 BC Head of Caesar, wearing the Etruscan gold crown.

Roman Republic. Denarius minted under the supervision of the Master of the Mint P. Sepullius Macer, 44 BC Head of Caesar, wearing the Etruscan gold crown.

At the beginning of 44 BC, the Senate of Rome granted Caesar a whole series of rights that a Roman had never possessed before. Caesar was appointed dictator for life, was allowed to wear the costume of the triumphator as often as he pleased, and to put his own image on coins like a Hellenistic ruler.

Roman Imperial Period, Hadrian (117-138), Aureus

Roman Imperial Period, Hadrian (117-138), Aureus

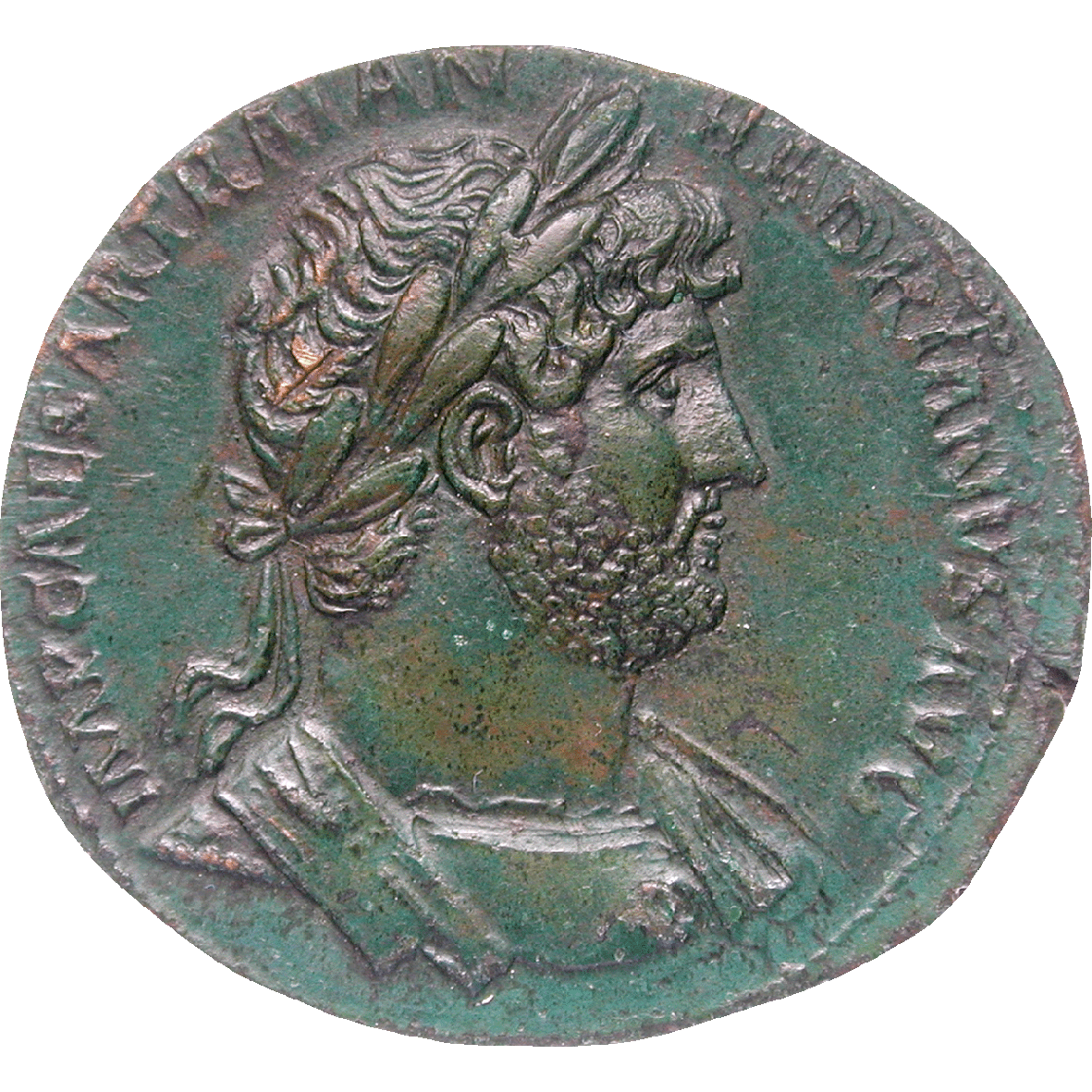

Roman imperial period, Publius Aelius Hadrianus, sestertius

Roman imperial period, Publius Aelius Hadrianus, sestertius

Roman imperial period, Diokletian (284-305), Argenteus

Roman imperial period, Diokletian (284-305), Argenteus

Solidus of Constantine I: the move from West Rome to East Rome

Roman Imperial Period. Constantinus I (307-337). Solidus, Trier, 314. Head of Constantinus with laurel wreath. Constantinus, standing right, dressed as general, holding world ball together with goddess Roma seated left of him with helmet, shield and spear.

Roman Imperial Period. Constantinus I (307-337). Solidus, Trier, 314. Head of Constantinus with laurel wreath. Constantinus, standing right, dressed as general, holding world ball together with goddess Roma seated left of him with helmet, shield and spear.

Constantinus, called the Great: we believe to know that he was pious, that he felt himself to be an instrument of the only, Christian God, and that he was obsessed with the desire to pave the way to power for Christians. But do we really know this?

We have countless testimonies from ancient historians on the person of Constantinus. But these historians were Christians, and they interpreted history in their own way: at some point in the not too distant future, the kingdom of God would come, and a person had to be judged according to the extent to which he promoted or hindered this. Good was the one who promoted, bad the one who hindered.

Bracteate: not the person is important, but the status within the hierarchy

Zurich. Fraumünster Abbey. Penny, 13th century. Inscription "ZVRICH", head of the abbess of Fraumünster with hood.

Zurich. Fraumünster Abbey. Penny, 13th century. Inscription "ZVRICH", head of the abbess of Fraumünster with hood.

In 853, Louis the German established a new monastic community of women in Zurich, which was to be presided over by his daughter Hildegard. The founding of convents to provide for unmarried women of the ruling families was a popular means of the time to enable the royal maidens to live a life befitting their status and at the same time to exercise direct rule over strategically important territories by means of a family member.

Thus, the abbess was now one of the greats of the empire, proud of her position, and this is exactly how - as abbess of the Fraumünster - she had herself depicted on her coins since the beginning of the 14th century. Which of the abbesses it was, however, who had the coin depicted minted, we will never know. The person takes a back seat to her status. What is important is not the person, but the office and the power he exercises.

Kratzquartier, Fraumünster and Münsterhof on the altarpiece by Hans Leu the Elder, c. 1500. Image source Wikipedia.

Kratzquartier, Fraumünster and Münsterhof on the altarpiece by Hans Leu the Elder, c. 1500. Image source Wikipedia.

Fresco by Paul Bodmer in the cloister with scenes of the founding legend of the Fraumünster. Image source Wikipedia.

Fresco by Paul Bodmer in the cloister with scenes of the founding legend of the Fraumünster. Image source Wikipedia.

Specially manufactured coin scales were used throughout the ages to check coins for full weight and authenticity. In the Middle Ages, easily collapsible folding scales were used to weigh coins and precious metals, as the number of minted varieties was almost unmanageable. The weights contained were not in a specific unit of measurement such as grams or ounces, but in the corresponding coin denominations: ducat, thaler or noble.

In Germany, most coin scales of the 16th-18th centuries originated in Nuremberg or Cologne and were veritable "export hits" of these cities. As late as the German Empire, small quick scales were still in general use for checking 5-, 10- and 20-goldmark pieces.

Charles V, painting by Titian. Photo Wikipedia

Charles V, painting by Titian. Photo Wikipedia

Louis XIV, the Sun King. Photo Wikipedia

Louis XIV, the Sun King. Photo Wikipedia

Renaissance and modern times: portraits of leading personalities

Charles V, King of Spain (1516-1556), Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (from 1519). Half Ducato, circa 1552. Armored bust of Charles with laurel wreath.

Charles V, King of Spain (1516-1556), Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (from 1519). Half Ducato, circa 1552. Armored bust of Charles with laurel wreath.

On this coin, Charles V mentions only a tiny section of his possessions, precisely those on which his power was essentially based. The New World, which we consider so decisive today, was not yet worth mentioning for Charles.

Louis XIV, King of France (1643-1715). Louis d'or 1693, La Rochelle. Head of Louis n. r. Weight: 6.7 gr.

Louis XIV, King of France (1643-1715). Louis d'or 1693, La Rochelle. Head of Louis n. r. Weight: 6.7 gr.

France's state budget was based on short-term loans from private individuals, which were repaid with high interest when taxes were received. If one did not want to drive it to national bankruptcy, only an iron austerity course remained. And Louis XIV was ready for it. He had a small booklet bound in red leather made for himself, in which he personally entered all income and expenditure. This way, the king could tell exactly how much money was in the treasury at any given time. And this strict control paid off. By 1664, France's finances were already the healthiest in Europe. The monarch was even able to record a surplus of half a million livres.

Groschen Zurich 1563: Symbols of the emerging trade

Until 1648, Zurich - as shown by the imperial eagle on the reverse of this coin - formally belonged to the Holy Roman Empire. For this reason, the city adhered to the provisions of the coinage regulations issued at the Imperial Diet of Augsburg in 1559 when minting its coins. According to it, the obverse should show the origin of the money, which was expressed here by the Zurich shield. Weight: 2.44 gr silver.

Until 1648, Zurich - as shown by the imperial eagle on the reverse of this coin - formally belonged to the Holy Roman Empire. For this reason, the city adhered to the provisions of the coinage regulations issued at the Imperial Diet of Augsburg in 1559 when minting its coins. According to it, the obverse should show the origin of the money, which was expressed here by the Zurich shield. Weight: 2.44 gr silver.

For this, the backs of the coins had to show imperial eagle and the value indication. The eagle bears a 3 on its chest, it was a 3 kreuzer coin, a so-called groschen.

For this, the backs of the coins had to show imperial eagle and the value indication. The eagle bears a 3 on its chest, it was a 3 kreuzer coin, a so-called groschen.

In 1587, there was dearth in Zurich; there were many unemployed and people were starving. The Zurich council therefore decided to employ people in road construction to alleviate the hardship - one of the earliest examples of state unemployment assistance in Switzerland. Under the direction of municipal foremen, whole armies of workers built the Zürichbergstrasse that year. For this hard work, the workers received six to seven shillings a day, about two groschen.

The daily working hours were precisely regulated. On construction sites, one had to work according to daylight, and there were differences between summer and winter working hours. For Zurich construction workers, the workday lasted from four in the morning to six in the evening in summer, while in winter the day's work began at daybreak. Work was interrupted by three rest breaks for breakfast, snack and supper. Each additional absence was penalized with two shillings.

City of Zurich end of 16th century

City of Zurich end of 16th century

Zurich around 1800 - 200 years later.

Zurich around 1800 - 200 years later.

The change: only numbers matter

The first exchange bank was founded in Amsterdam in 1600. In the 17th century, the importance of the bill of exchange increased abruptly. This book is a guide and reference book on how bills of exchange had to be drawn up in various cities.

The first exchange bank was founded in Amsterdam in 1600. In the 17th century, the importance of the bill of exchange increased abruptly. This book is a guide and reference book on how bills of exchange had to be drawn up in various cities.

Herbach, Johann Caspar: Introduction to the Thorough Understanding of the Action of Bills of Exchange, 1716

The bill of exchange is personified by the person above with the map of Europe in his hand. Under the eye of God and the crown. Sign that God and right supports this activity. Next to her, the time (how long is the bill valid?), the compass (where is it cashed?), the mirror (warning to be careful) and the cornucopia as a symbol of profit. Thrown to the ground is the lyre, symbol of idleness. Below, Mercury, god of trade, and in the background, a bustling commercial city.

Since Napoleon the number has priority on the coins

Republik Frankreich, 5 Francs An 8.

Republik Frankreich, 5 Francs An 8.

This coin was issued shortly after the Revolution. The new calendar was valid from 1792, i.e. "An 8" is the year 1800. Napoleon reintroduced the Gregorian calendar in 1806.

Switzerland. Helvetic Republic. Neutaler at 40 Batzen 1798.

Switzerland. Helvetic Republic. Neutaler at 40 Batzen 1798.

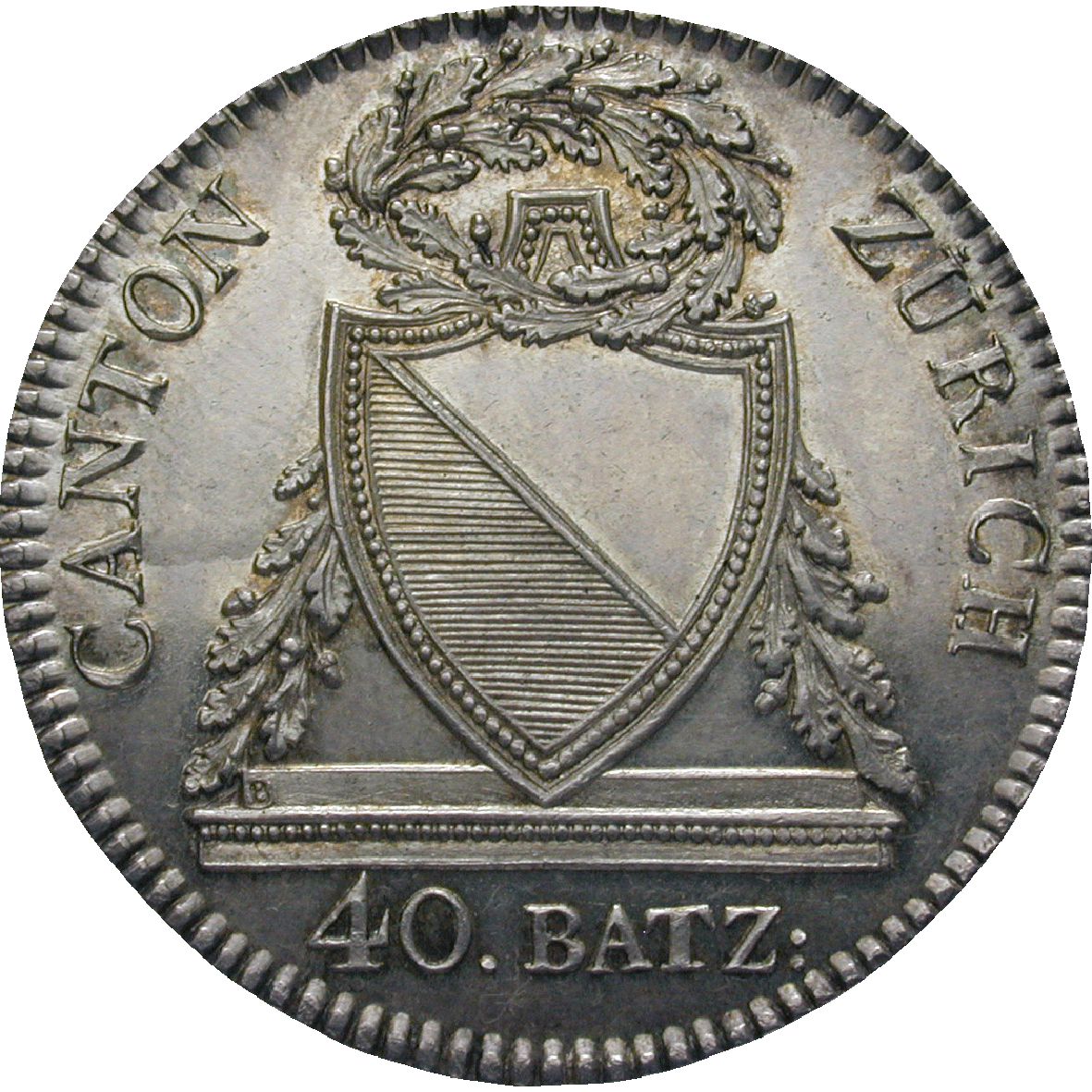

40 Batzen Zürich 1813

40 Batzen Zürich 1813

Swiss Confederation. 20 francs 1883, Bern. Personification of Helvetia with diadem and alpine rose wreath. Rs. Swiss coat of arms in wreath of oak and laurel leaves.

Swiss Confederation. 20 francs 1883, Bern. Personification of Helvetia with diadem and alpine rose wreath. Rs. Swiss coat of arms in wreath of oak and laurel leaves.

Swiss Confederation.100 francs 1925, Bern. Bust of a woman in rural costume n. l. before mountain world. Rs. Swiss cross in glory above value and year, below branch of alpine roses.

Swiss Confederation.100 francs 1925, Bern. Bust of a woman in rural costume n. l. before mountain world. Rs. Swiss cross in glory above value and year, below branch of alpine roses.

The MoneyMuseum is primarily interested in how the transition from heads to tails on the coin came about. "Natural development", say some, and fail to recognize the great upheavals that continue to have an impact to this day. The following contributions serve to explain this upheaval.

From Euclidian geometry to modern mathematics. Until well after 1500, Euclid was considered the textbook of arithmetic par excellence, but in the 17th century a whole new kind of mathematics developed.

Rhythm sensation: In time with money - the beat rhythm. Has the beat rhythm always existed, or when did it come into being? The author investigates the cause and finds something surprising.

City air makes free - money is everywhere. The key to the development of the one, exclusive and pure means of exchange lies in urban development, which took a very special course exclusively in Europe. Here at the example of Zurich.

The Bockelmann Theses prepared and explained for oral dialogue.