The Social Contract

Citizens pay taxes and receive provision, security and protection of freedom and life from the state in return. Over generations. This is called a social contract or intergenerational contract.

The contract between the generations has been broken. Not only has the current generation spent all its money - including that of its descendants - but it has even taken on debts that the next generation will have to pay. Of course, inequality has decreased globally in recent decades, if you include China, India and all the faraway countries. That is great progress. But I'm talking about Europe, and possibly the USA. In our country, it makes sense to reflect on the beginnings of the discussion on the social contract and to gain perspectives for the future. Because here everything is in upheaval.

Drei Generationen

Drei Generationen

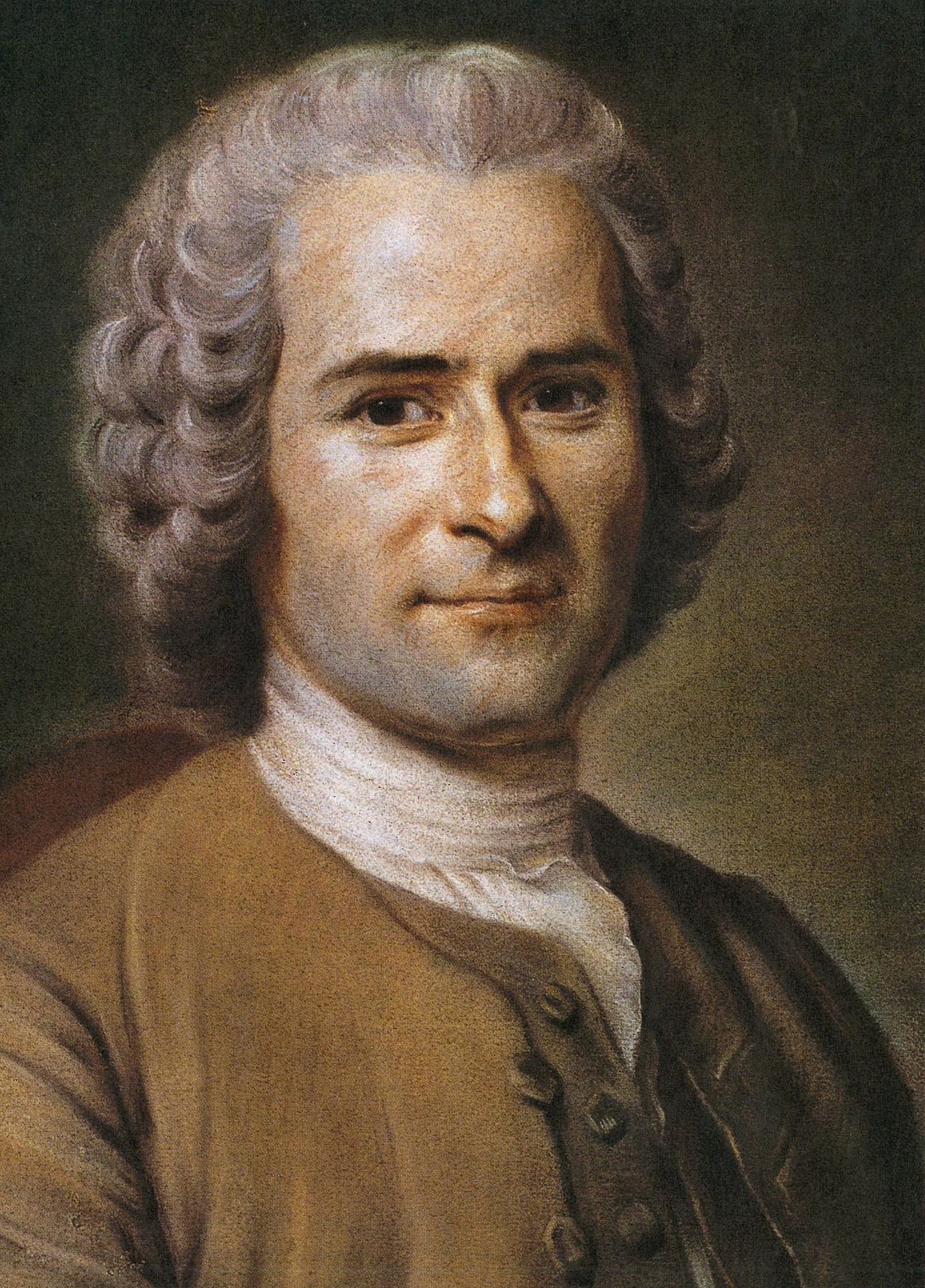

The following are the thoughts of philosophers Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jaques Rousseau on this subject, whose thoughts eventually led to the French Revolution and American Declaration of Independence.

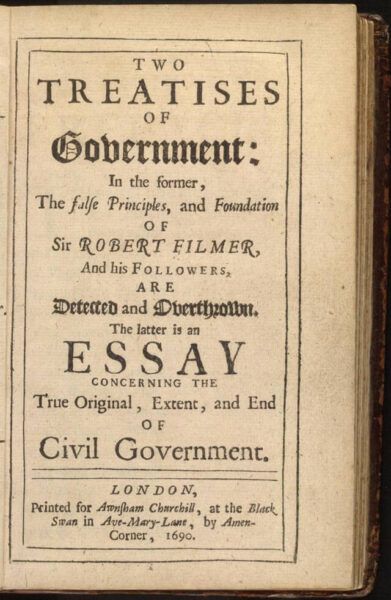

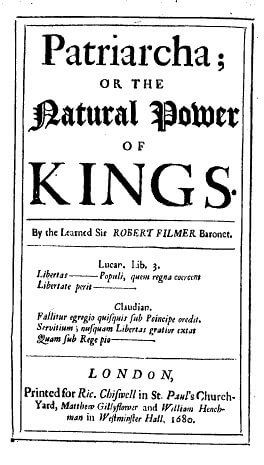

John Locke, Two Treatises of Government: In the former, The false Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and his Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The latter is an Essay Concerning the True Original, Extent, and End of Civil Government.Gedruckt in London, 1690.

John Locke, Two Treatises of Government: In the former, The false Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and his Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The latter is an Essay Concerning the True Original, Extent, and End of Civil Government.Gedruckt in London, 1690.

Is man by nature good or evil? Is he benevolent toward others or does he envy their possessions? And what form of government is best suited to ensure the security and prosperity of its citizens? These were the questions many European thinkers asked themselves beginning in the 17th century. One prominent idea was that of contractualism, that is, the notion that people voluntarily join together as a body of states by means of a kind of social contract.

The philosophers Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jaques Rousseau all grappled with this idea, but came to different conclusions.

How Locke imagined man in the state of nature and what the ideal social contract looked like for him is what we will deal with here first.

The state of nature

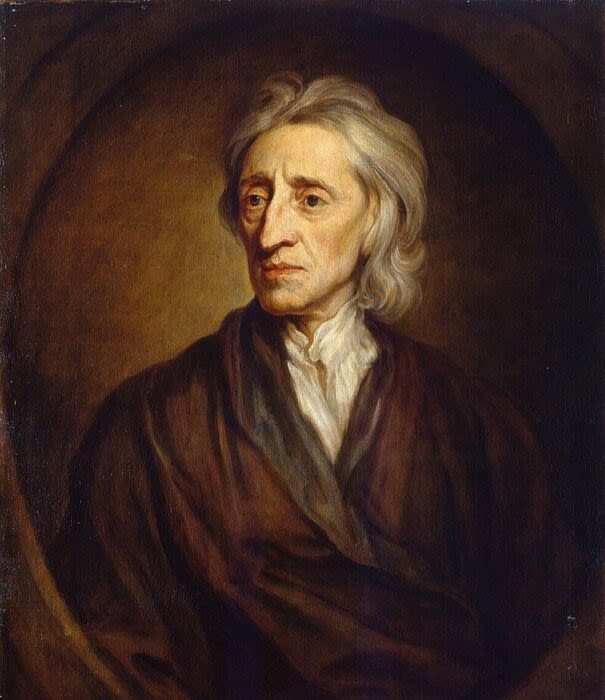

Portrait of John Locke by Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1697.

Portrait of John Locke by Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1697.

John Locke (1632-1704) and Thomas Hobbes (1578-1679) lived around the same time. And what a time it was! The 17th century was marked by extreme political upheaval. Within a few decades, England saw the execution of the monarch Charles I, a republic, a military dictatorship, a return to monarchy, and finally a peaceful revolution. Given this tremendous turmoil and the many different models of government that were experimented with here in a short period of time, it hardly seems surprising that they were so intensely engaged with the subject.

Hobbes' thinking is strongly influenced by the experiences of the bloody English civil war and conceives the state of nature as a war-like, anarchic chaos, as a "war of all against all". The only way to bring this state under control is with the help of an absolutist sovereign who can enforce order even with the sword if necessary. For Locke, on the other hand, certain laws apply even in the state of nature, first and foremost the law of reason. He believes that people can behave rationally of their own free will, which means, for example, not harming others or respecting their property.

Where does "property" come from?

An interesting question is how man comes to property in Locke's conception. In the state of nature, everything belongs to everyone, or rather everything belongs to God. However, if a man does work, according to Locke, for example by picking an apple and then eating it, he makes this common good his own, he literally appropriates the apple. If he does this on a large scale, he can cultivate fields, exchange surplus natural goods for money and build up private property. If man in the state of nature already acts rationally and can even build up a functioning economic system, however, an important question arises: Why does he then still need the state?

Well, although people in Locke are able to behave in a peaceful and civilized manner under certain conditions, this does not mean that they will always do so. There is always the danger that they will become envious and want to take property from others. So they band together to better protect their own lives, freedom and property. A little less freedom, a little more security.

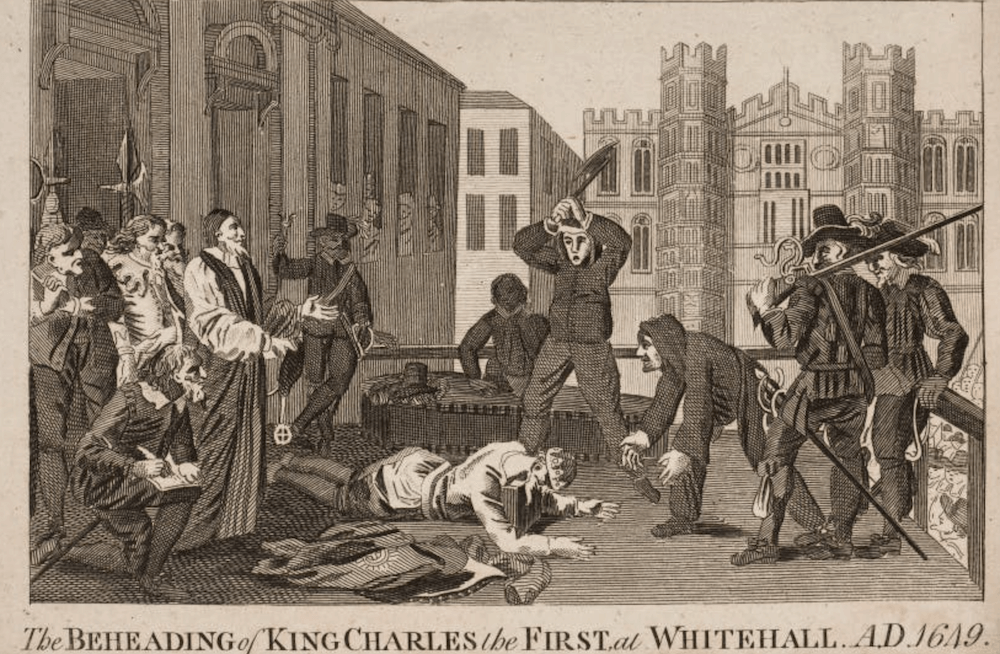

King Charles I of the House of Stuart was king of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1625 to 1649. His attempts to introduce a uniform church constitution in England and Scotland and to rule without parliament in the spirit of absolutism triggered the English Civil War, which ended with Charles' execution in 1649 and the temporary abolition of the monarchy (Wikipedia).

King Charles I of the House of Stuart was king of England, Scotland and Ireland from 1625 to 1649. His attempts to introduce a uniform church constitution in England and Scotland and to rule without parliament in the spirit of absolutism triggered the English Civil War, which ended with Charles' execution in 1649 and the temporary abolition of the monarchy (Wikipedia).

Contemporaries already used the term Glorious Revolution in deliberate contrast to the turmoil of the English Civil War, which had ended with the execution of King Charles I and the establishment of a republic under Oliver Cromwell. By contrast, the overthrow of 1688/1689 was comparatively bloodless.

Contemporaries already used the term Glorious Revolution in deliberate contrast to the turmoil of the English Civil War, which had ended with the execution of King Charles I and the establishment of a republic under Oliver Cromwell. By contrast, the overthrow of 1688/1689 was comparatively bloodless.

Kingdom of England, William III and Mary II, 5 guineas 1692. Introduced in 1663, the guinea was the main gold coin of England until 1816. The obverse of this guinea shows the English kings William III and Mary II, who ruled the country equally (1689-1702).

Kingdom of England, William III and Mary II, 5 guineas 1692. Introduced in 1663, the guinea was the main gold coin of England until 1816. The obverse of this guinea shows the English kings William III and Mary II, who ruled the country equally (1689-1702).

The first of Locke's two treatises is directed against this writing by the English philosopher Robert Filmer. Filmer defends the absolute divine right of the English monarchy.

The first of Locke's two treatises is directed against this writing by the English philosopher Robert Filmer. Filmer defends the absolute divine right of the English monarchy.

The first of Locke's two treatises is directed against the writing of the English philosopher Robert Filmer. Filmer defends the absolute divine right of the English monarchy.

We see, then, that Locke's social contract is not a life-and-death necessity, as it was for Hobbes, but rather a voluntary step that promises to benefit the individual in the long run. That in Locke's thinking the task of the state is primarily to protect the integrity and freedom of the individual explains why he is so often cited as a founder of liberalism.

No to God's Grace

Now that we have clarified why life in the state is preferable to life in the state of nature, the question arises as to who may govern it and why. From the first of his Two Treatises on Government, we already know who Locke does not consider legitimate rulers: Monarchs who invoke God's grace. The thesis that God gave Adam absolute dominion over the world and that modern kings can therefore indirectly invoke this right within the framework of a hereditary monarchy is false. God only gave Adam the right to rule over the world and the animals, but not over other people.

Thus, a government does not receive its legitimacy from God, but by fulfilling its task of protecting people's freedom. If it fails to do so, it forfeits its claim to power and may be deposed, by force if necessary. For Locke, it is of secondary importance whether the government takes the form of a monarchy, a republic, or some other form of state, as long as it abides by the rules of the contract and does not become tyrannical. For - and this is fundamentally important - the treaty applies in both directions.

From left to right, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson draft the Declaration of Independence. Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, 1900.

From left to right, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson draft the Declaration of Independence. Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, 1900.

The Right to Revolution and the American Declaration of Independence

The idea that a bad government could break treaties and be terminated for it was revolutionary! It provided the American colonists with the theoretical foundation to break away from the rule of Great Britain - and to denounce George III's treaty. In the opinion of the emigrants, George III had not fulfilled his duty to provide for the common good of his citizens overseas, but had made life difficult for them for years. The list of "grievances" that the drafters of the Declaration of Independence attached in 1776 was long. The colonists complained about having to feed the king's British soldiers, they complained about ever new taxes and duties without getting a parliamentary say in return, about unfair court proceedings and much more. The government under George III had become a bad government for them.

From Locke's writings, they were now finally able to derive a rationale as to why this gave them the right to revolution. Thus, some passages from Locke's work were incorporated almost verbatim into the Declaration of Independence, which states:

2-Dollar bill of 1776

2-Dollar bill of 1776

The following truths we hold to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted among men, deriving their legitimate power from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government proves inimical to these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute new government....

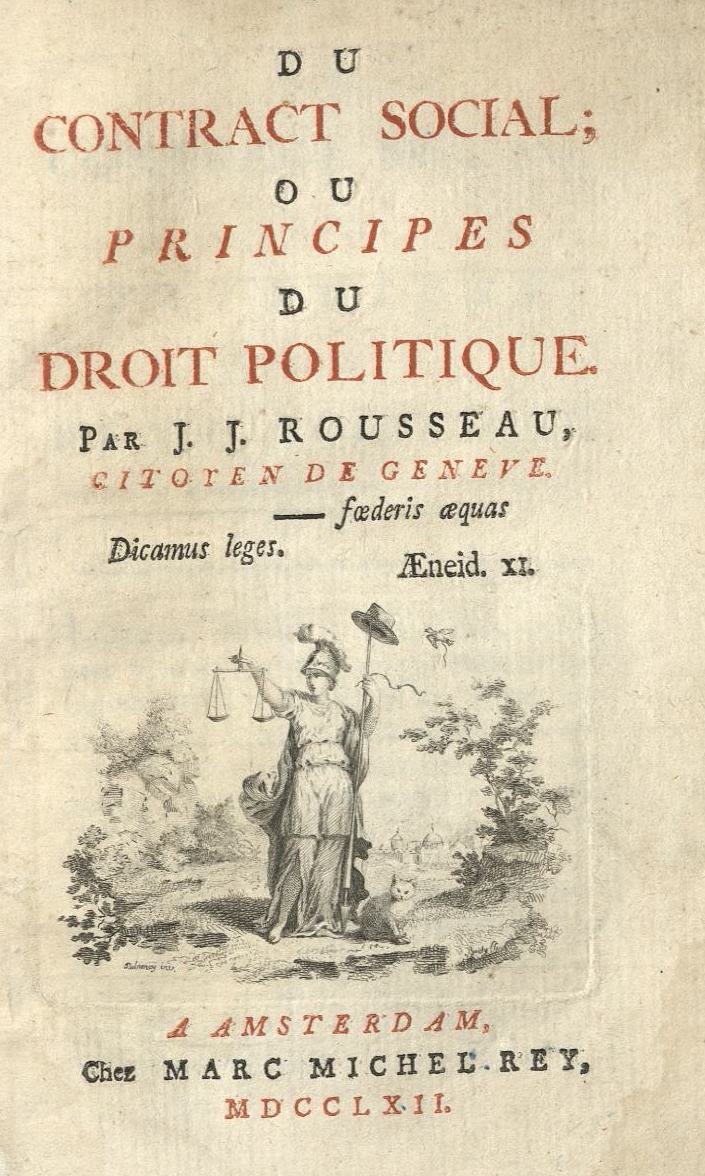

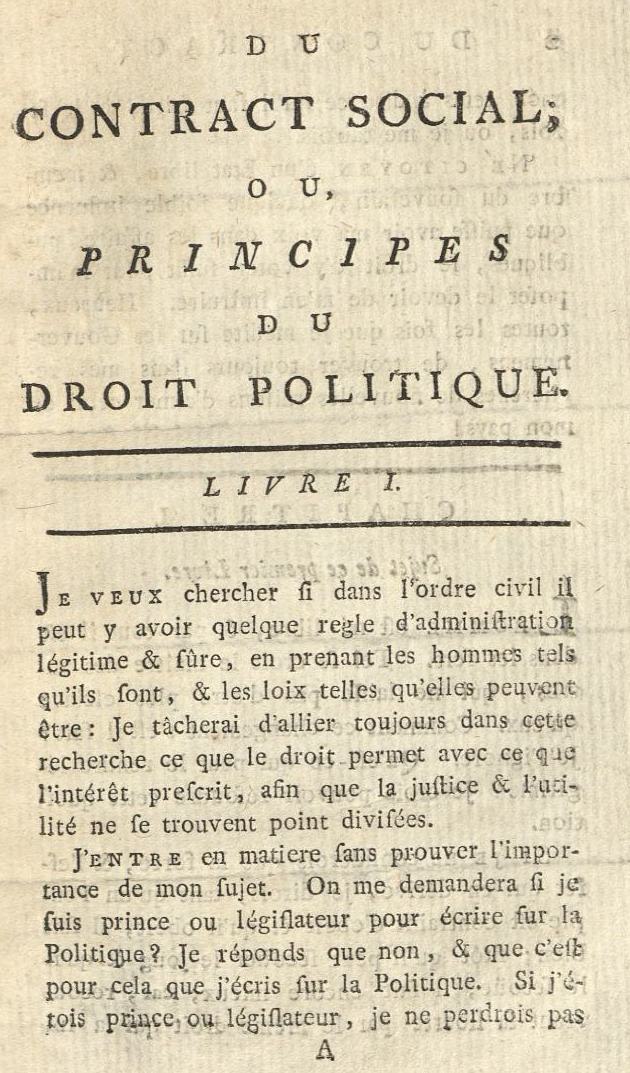

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Du contrat social ou Principes du droit politique. Gedruckt in Amsterdam 1762 bei Marc Michel Rey.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Du contrat social ou Principes du droit politique. Gedruckt in Amsterdam 1762 bei Marc Michel Rey.

The average Western European owns around 10,000 things. Collectors of all kinds have more, of course. Many people feel crushed by this, and that's why minimalism is the trend par excellence right now; people don't want to burden themselves with a lot. At the same time, many are looking for community with others, coupled with a "natural" lifestyle in the countryside or at least with their own small plot for urban gardening between car lanes in the inner city.

But naturalness and minimalism were already "in" almost 300 years ago. The French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau was of the opinion at the time that man is good in a state of nature and that only culture brings out the evil in him. So either you live in the primal state or you have to come up with the most "natural" form of political organization possible in order to live a morally good life. Rousseau explained this in detail in 1762 in his "Social Contract" - which was immediately banned.

Rousseau and the world of absolutisms

The reason for this prohibition is quite simple: In Rousseau's utopia, there is no need for God or aristocrats, but only one sovereign, namely the people. In a thoroughly aristocratic world like Rousseau's, these were unacceptable and dangerous thoughts. We are in the world of absolutism, Louis XV decisively leads the scepter, whoever can, lives in luxury, castles are built and splendid festivities are celebrated. And then comes this Rousseau.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva in 1712, his mother died after his birth, his father, a respected watchmaker, taught the boy a love of literature - until he went into hiding after a fistfight with an (aristocratic) officer, thus pushing his son into an unsteady life. The young Rousseau was a difficult, idiosyncratic character, who sometimes hired himself out as a teacher, then put up with being the secretary and lover of a rich lady. He educated himself autodidactically and moved from place to place across France. Until he had an "epiphany" in 1749, as he himself called it.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was born in Geneva in 1712, his mother died after his birth, his father, a respected watchmaker, taught the boy a love of literature - until he went into hiding after a fistfight with an (aristocratic) officer, thus pushing his son into an unsteady life. The young Rousseau was a difficult, idiosyncratic character, who sometimes hired himself out as a teacher, then put up with being the secretary and lover of a rich lady. He educated himself autodidactically and moved from place to place across France. Until he had an "epiphany" in 1749, as he himself called it.

The prize question: Is man by nature good or evil?

By chance, Rousseau came across a prize question that would henceforth define his life. The Academy of Dijon asked in a newspaper, "Has the restoration of the sciences and arts helped to purify morals?" Any intellectual would have immediately answered in the affirmative. But Rousseau was a stubborn and maverick man and loved to provoke. So now he was taking on France's entire elite and answering the question: No! Man was good in his original state and only became evil and vicious through human coexistence - and thus also through culture. Curiously, however, Rousseau also met with approval; he became one of the most widely read authors in Europe overnight and won first prize in the competition. From then on, the 37-year-old Rousseau made himself comfortable in the role of enfant terrible and cultivated it until his death in 1778.

The social contract: the basis of an idea

Rousseau published plays and essays in which he repeatedly emphasized that only the establishment of a community would lead to greed and excessive needs among people. In 1762, he developed a political manifesto from this basic assumption, his main theoretical work: On the Social Contract or Principles of Political Law.

Wisely, he had it printed not in France but in the more liberal Netherlands, in Amsterdam by Marc Michel Rey. Rey was a promoter of the literature of the Enlightenment, as we call this epoch, in which again and again individuals had ideas like Rousseau's, who fought against the previous mainstream and put reason above tradition. Rey had already published other writings by Rousseau, but with the "Social Contract" he earned not only fame but also trouble. The work was immediately banned not only in France, Geneva and Bern, but also in the Netherlands itself. Rousseau had to flee and was given asylum by Frederick the Great of Prussia.

We have here a first edition of the Social Contract, which caused a furor throughout Europe and was to influence philosophers, political thinkers, and eventually even constitutional lawyers and sociologists for centuries. But how could someone who saw human community as the cause of all evil design a political organization for a good society?

Freedom is not equal to freedom

In nature, man is initially good, according to Rousseau. He lives in "natural freedom" and only his own strength sets him limits. Then, at some point, property relations arose, and that's when the problems began. For "all-devouring ambition," "artificial passions," and the "addiction to make one's fortune at the expense of others" are evils that arose from "the first effect of property and the inseparable corollary of the inequality that arises."

Rousseau describes this very vividly: "The first person who surrounded a piece of land with a fence and had the idea of saying 'This is mine,' and who found people who were simple-minded enough to believe him, was the actual founder of civil society. How many crimes, wars, murders, how much misery and terror the human race would have been spared if someone had pulled out the stakes and called out to his fellow men: 'Beware of believing the deceiver; you are lost if you forget that while the fruits belong to all, the earth belongs to no one.'" Marx? Lenin? Mao? Rousseau!

But Rousseau was clear: to survive in a dangerous world with wild animals and natural disasters, a community is essential. But how to prevent the progressive decline of mores? In this community, citizens should be given as much territory as they need.

Natural liberty had meant: we may desire to take anything we want only if we can. Civil liberty meant: we respect that others have something too, just as they respect our property; so we are no longer allowed to desire everything.

This is the social contract that all members conclude with each other. One can also say: First, all individuals cede their potential rights to the community (the sovereign), which then in turn allocates property to them. The advantage? Not everyone has to defend his property for himself alone, but all stand up for each other.

This reason-soaked theory knows only one legitimate basis of power: the general will, volonté générale. This will, which emanates from all individuals, can only want what is best for the community and is thus detached from subjective interests. It exists only because the individual citizens have in a sense given up their will and their rights and transferred them to this public person.

Sounds good. But are people like that? Well, Rousseau is also clear: If citizens were to claim more rights than duties for themselves, this would eventually lead to the downfall of the state. Ergo, the community is allowed to force a member to the common will, "which means nothing else than forcing him to be free," as Rousseau puts it. In all of these constructs, there is neither the divine right nor the traditional society of estates.

Maximilien Robespierre (anonymous portrait, c. 1793, Musée Carnavalet)

Maximilien Robespierre (anonymous portrait, c. 1793, Musée Carnavalet)

The fall of Robespierre at the National Convention on July 27, 1794

The fall of Robespierre at the National Convention on July 27, 1794

With this, as I said, the good Rousseau had initially overstepped the mark. But the idea was printed, the thought could no longer be suppressed. The seed was planted by the suffering of the common people and the enlightened thoughts of a few intellectuals and soon took root in the French Revolution.

Robespierre was the radical champion of the revolution and was strongly inspired by Rousseau's "Community Contract." Whether the result was the society that Rousseau had in mind? Probably not. He was then, after all, very much a theorist and really just wanted to have his peace. A work that quite pragmatically developed a realistic and realizable social order could hardly have been expected from him. But his approach has been taken up again and again since it was launched in 1762.