Numismatics

Books Collection MoneyMuseum

The birth of Greek numismatics

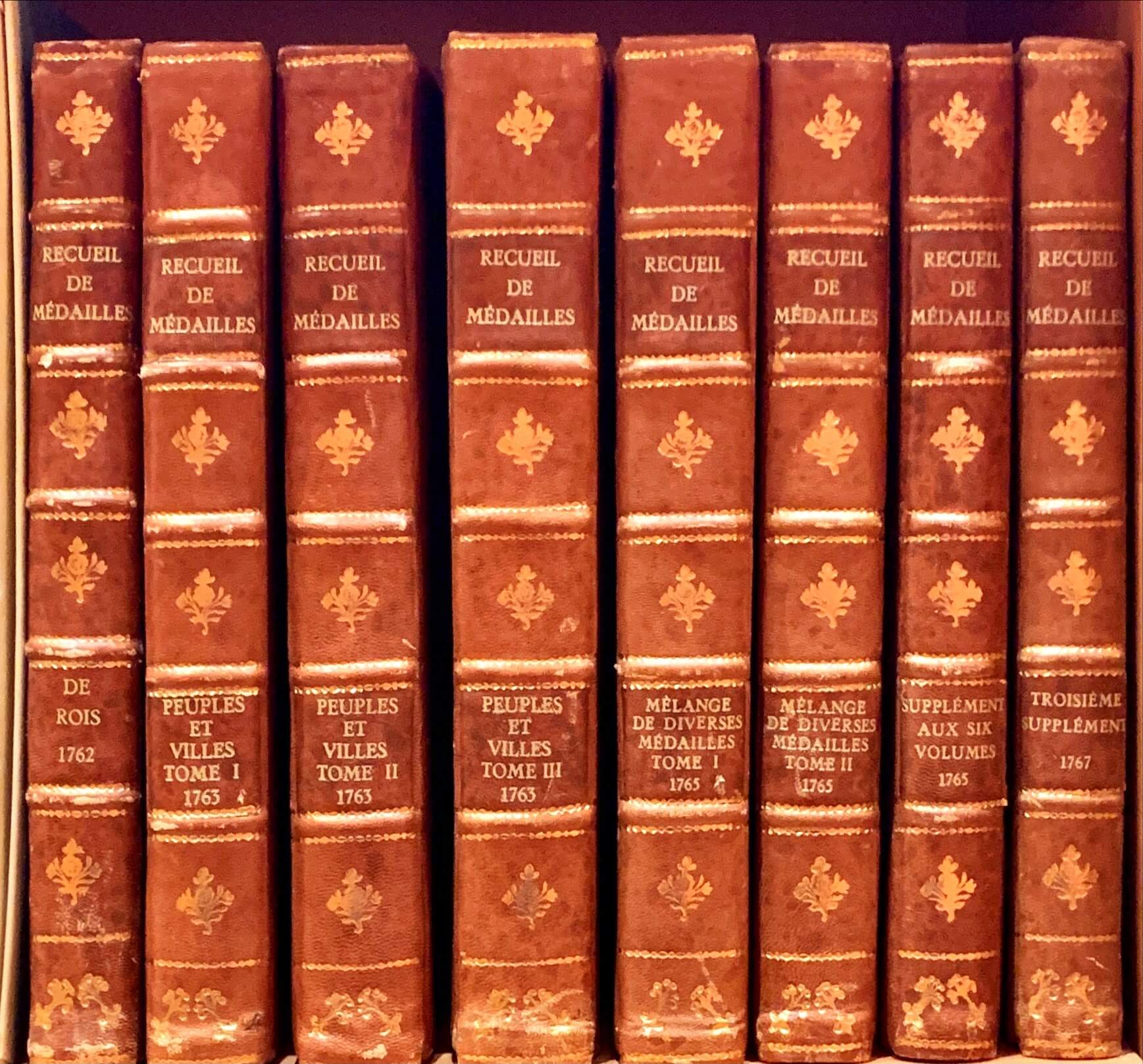

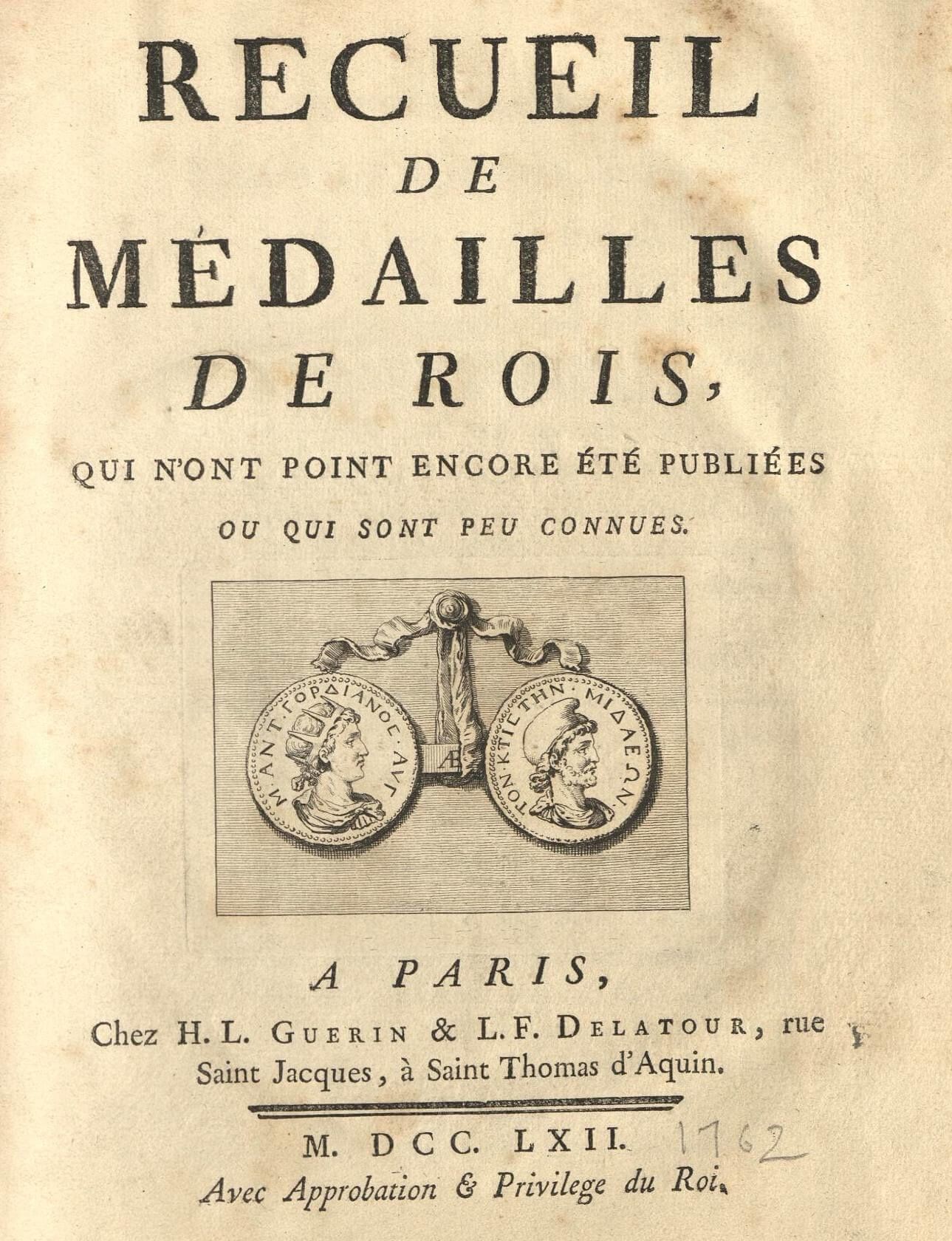

Joseph Pellerin: Recueil de médailles

The volumes of Joseph Pellerin's Recueil de médailles, published from 1762 onwards, are nothing less than the birth of Greek numismatics.

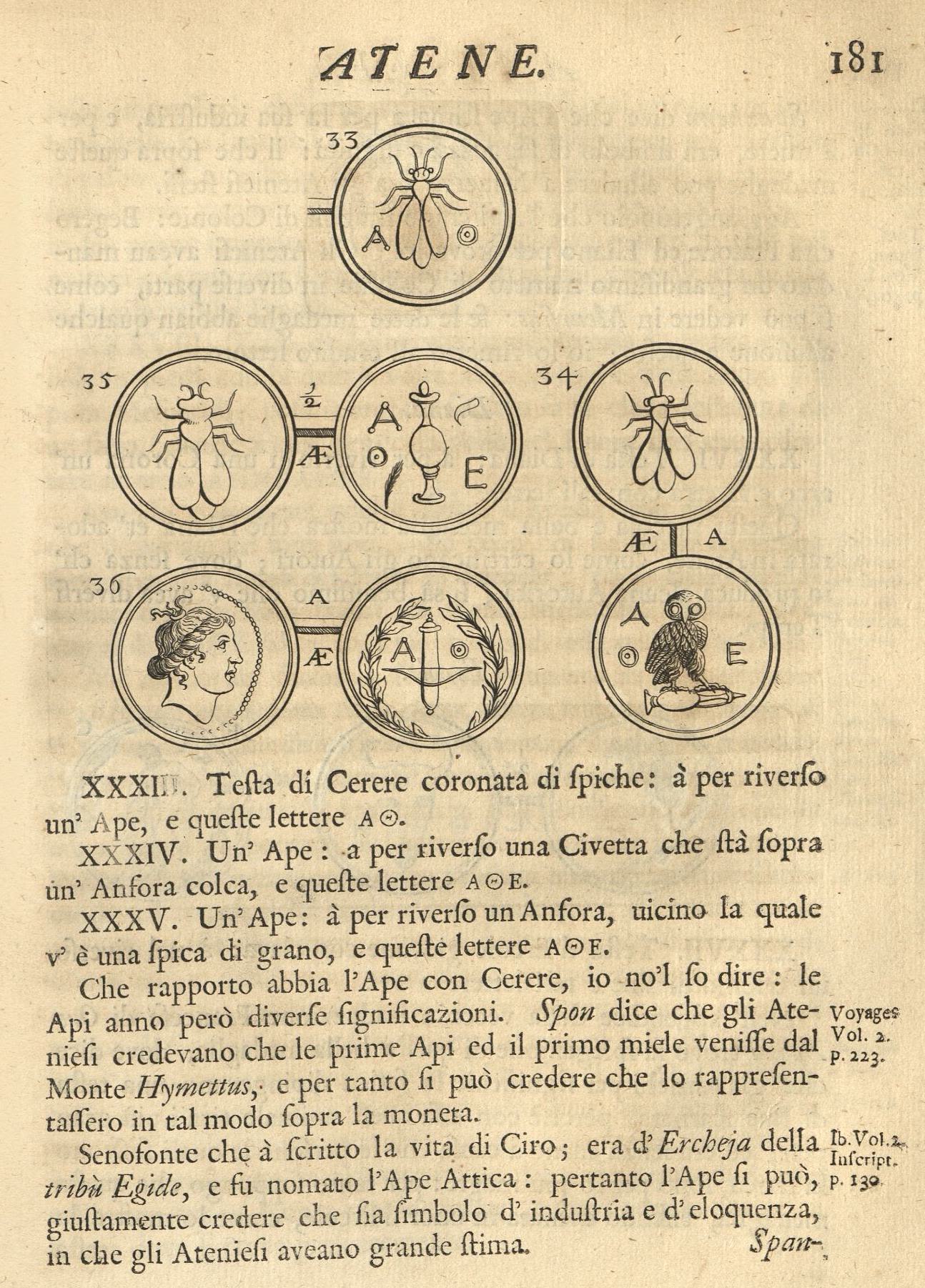

There were plenty of catalogs of ancient coins before that, but most of them dealt with the Roman world. Joseph Pellerin (1684-1783) was the first who can be said to have scientifically and systematically recorded and catalogued coins from the entire Greek world. He was helped by his own massive collection of over 33,000 coins - the largest and most valuable private collection of Greek coins that had existed up to that time.

What is remarkable about the volumes is the geographical arrangement of the catalogs. It was the basis for the scientific order that Joseph Eckhel later used in his works and that is still standard in museum collections and catalogs of ancient coins as Eckhel's system.

The volumes were repeatedly followed by supplements and additions in 1778, so that there are ten volumes in total, of which the first eight are in the MoneyMuseum Collection.

Pellerin sold his coin collection in 1776 to King Louis XVI, who gave him a full 300,000 livres for it. To stay with Pellerin's naval career: That's about the cost of half a frigate fit for war at the time. To this day, his important collection is part of the Cabinet des Médailles of the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

He is the grandfather of Greek numismatics in a double sense: on the one hand, because he was engaged in numismatics until his death at the then biblical age of 99. On the other hand, Joseph Eckhel is considered by many to be the father of the scientific study of Greek coins and the classification system named after him - if this is so, Pellerin, on whose work Eckhel builds, would be the grandfather of Greek numismatics.

Del Tesoro Britannico: A composer tries his hand at the first catalog of British collections

Del Tesoro Britannico, Band 1, London, 1719.

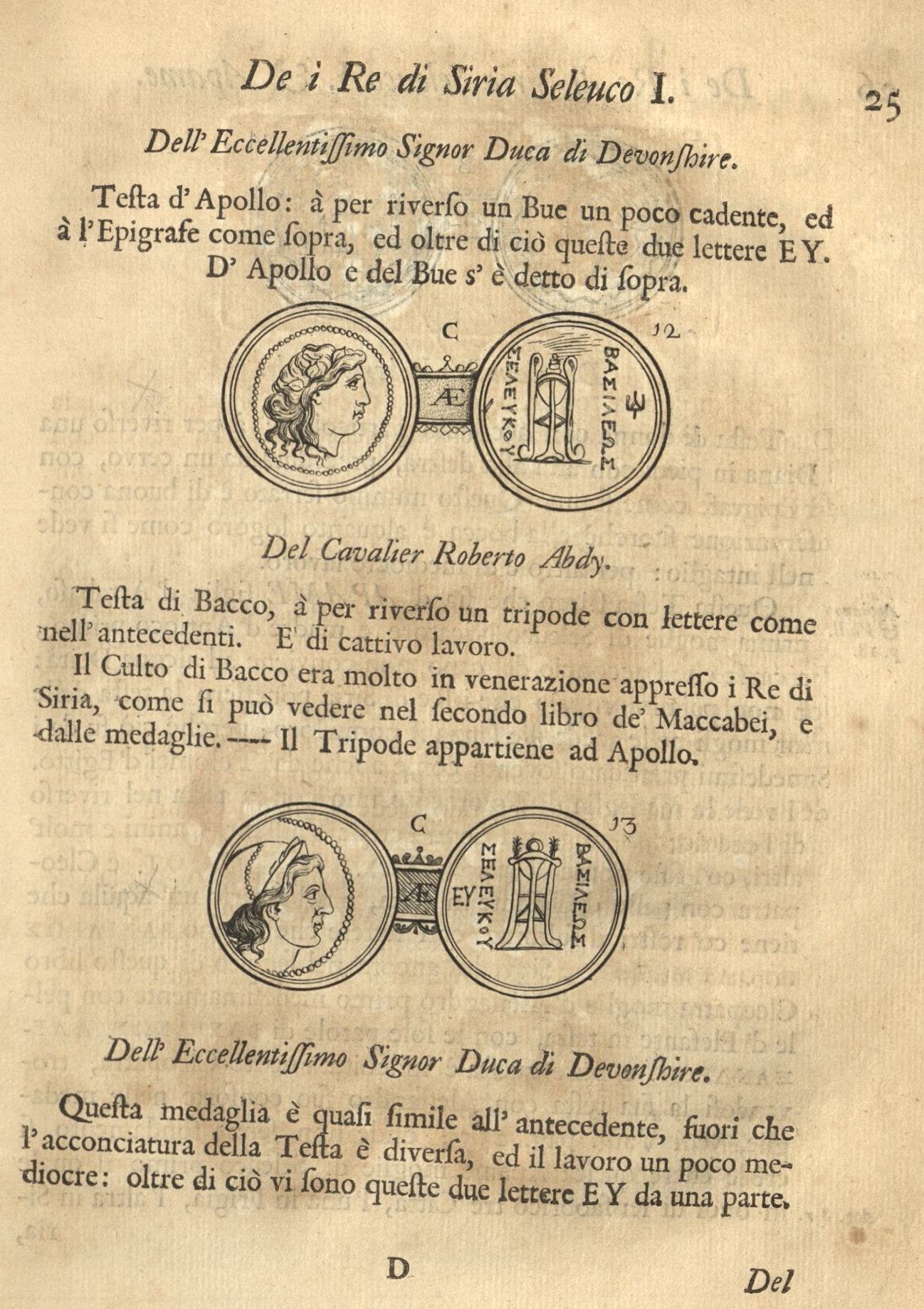

In the early 18th century, collecting antique coins was very popular and was part of good manners in aristocratic and educated circles. People who knew about it were in demand and, with the support of princes, wrote catalogs of their collections. Nicola Francesco Haym (1678 - 1729) also wanted to tackle such an ambitious project. His Tesoro Britannico, as he planned, was supposed to fill a gap and cover the ancient coins in the English collections, because they had not been appreciated with such a compendium until then. He found many supporters for this among the distinguished collectors in England, for he was well connected. He was a well-known and courted musician and composer.

The first catalog of coins in British collections, written by Haym, has been something of a pastime. In the library we have the first volume, published in 1719. The texts are entirely in Italian, an English version was published in the same year. The title "Treasures of England" is explained by the fact that Haym intended even more than "only" to cover the ancient coins in the British Isles, but also gems, statues and other antiquities in Great Britain.

The quality of the catalog, however, did not correspond to what the many high nobility pre-orderers, whom Haym proudly had invited, had imagined. He himself wrote in the preface that, as a Roman, knowledge of antiquity was naturally in his nature, but perhaps he should not have relied on this - his father, after all, was not a true Roman, but born in Bavaria, which also explains the surname Haym. In any case, according to one critic, his catalog was full of "egregious errors." In the following year, the second volume, which was visibly revised in many points, was published, but then it was already over. Thus the project remained incomplete. Haym devoted the following years instead to a six-volume history of music and eight volumes on rare Italian books.

Coins as a historical source

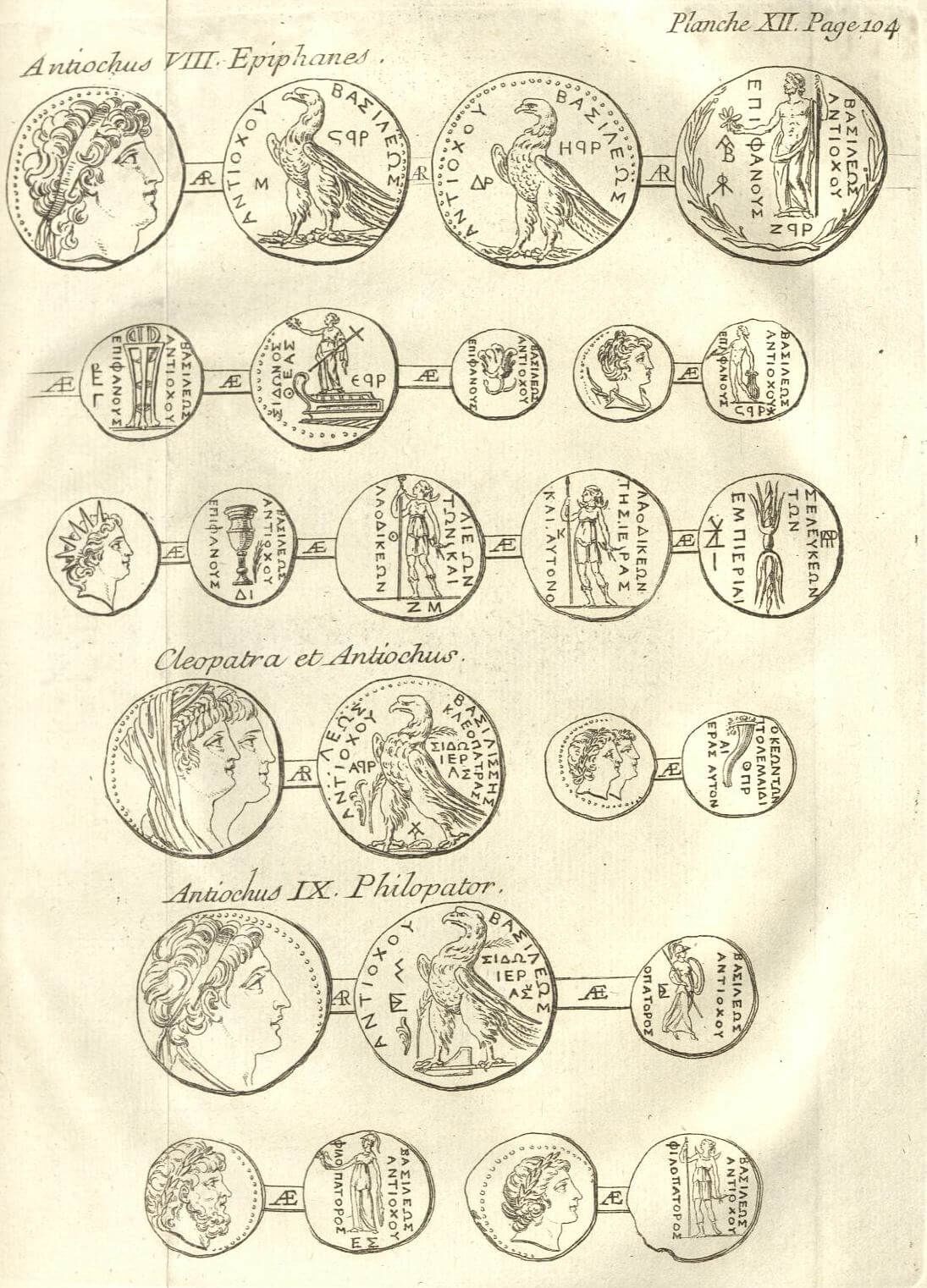

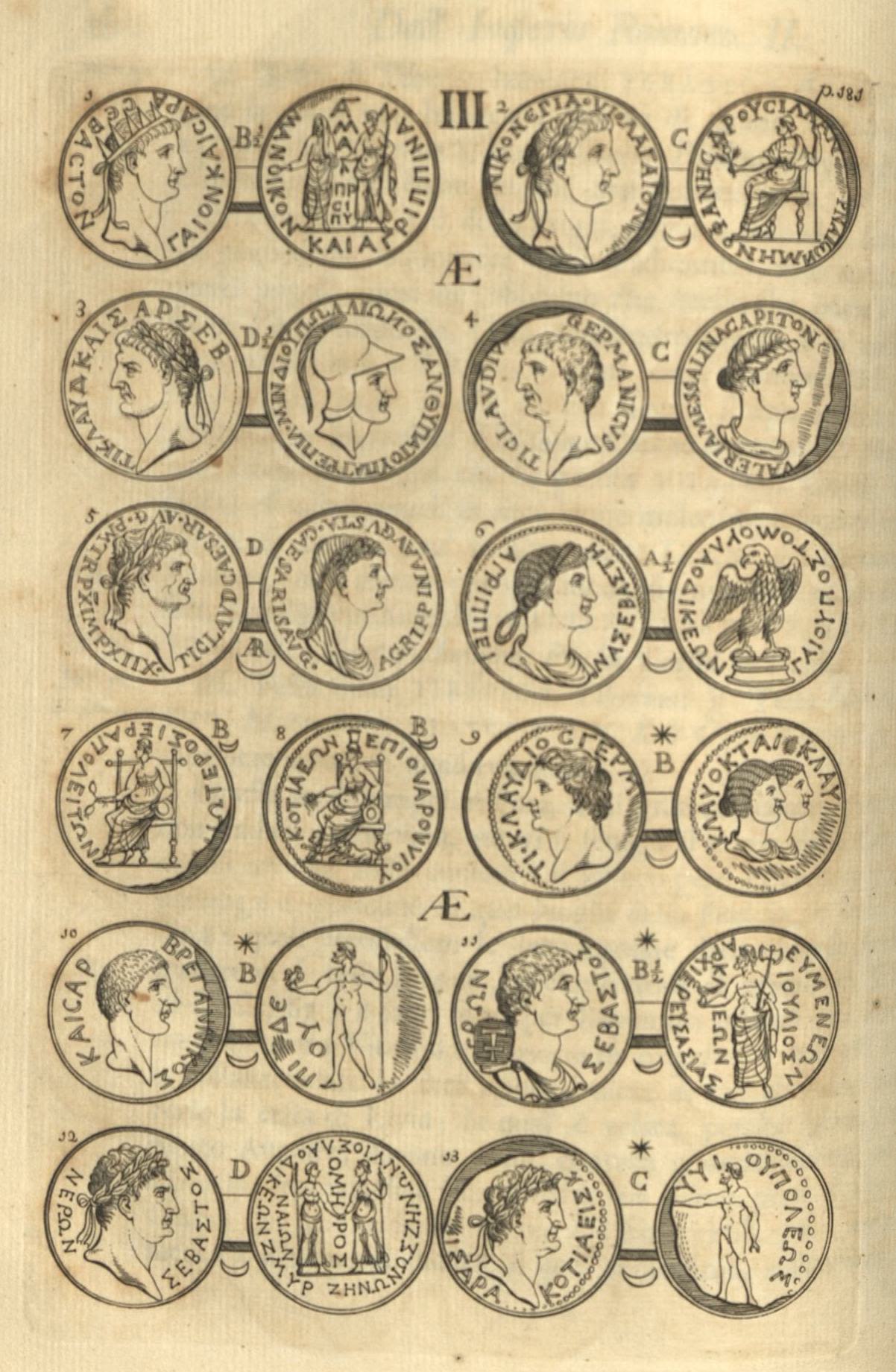

Erasmus Froelich, Annales compendiarii regum et rerum Syriae: numis veteris illustrat. Gedruckt in Wien 1744

„And the Bible is right after all" was the title of a book published in 1955. Its author wanted to prove that with the help of archaeology the ultimate proof for the truth of the events described in the Bible could be provided. Even if one can have different opinions about the theses put forward in it, the book was a success. It was translated into 20 languages and several million copies were published.

One reason for the widespread distribution of the book could be that since the Enlightenment, people have always asked themselves and continue to ask whether modern research and faith cannot be reconciled. One of those who tried this already in the 18th century was the Jesuit Erasmus Froelich.

In 1746, Maria Theresa appointed him to the Theresianum, a grammar school she had just founded to enable destitute boys to acquire a higher education without having to consecrate their lives to a Catholic order. Froelich determined the coins together with two colleagues and published with them the first printed index of the entire coin collection with 150 illustration plates.

The Books of Maccabees - Real or False?

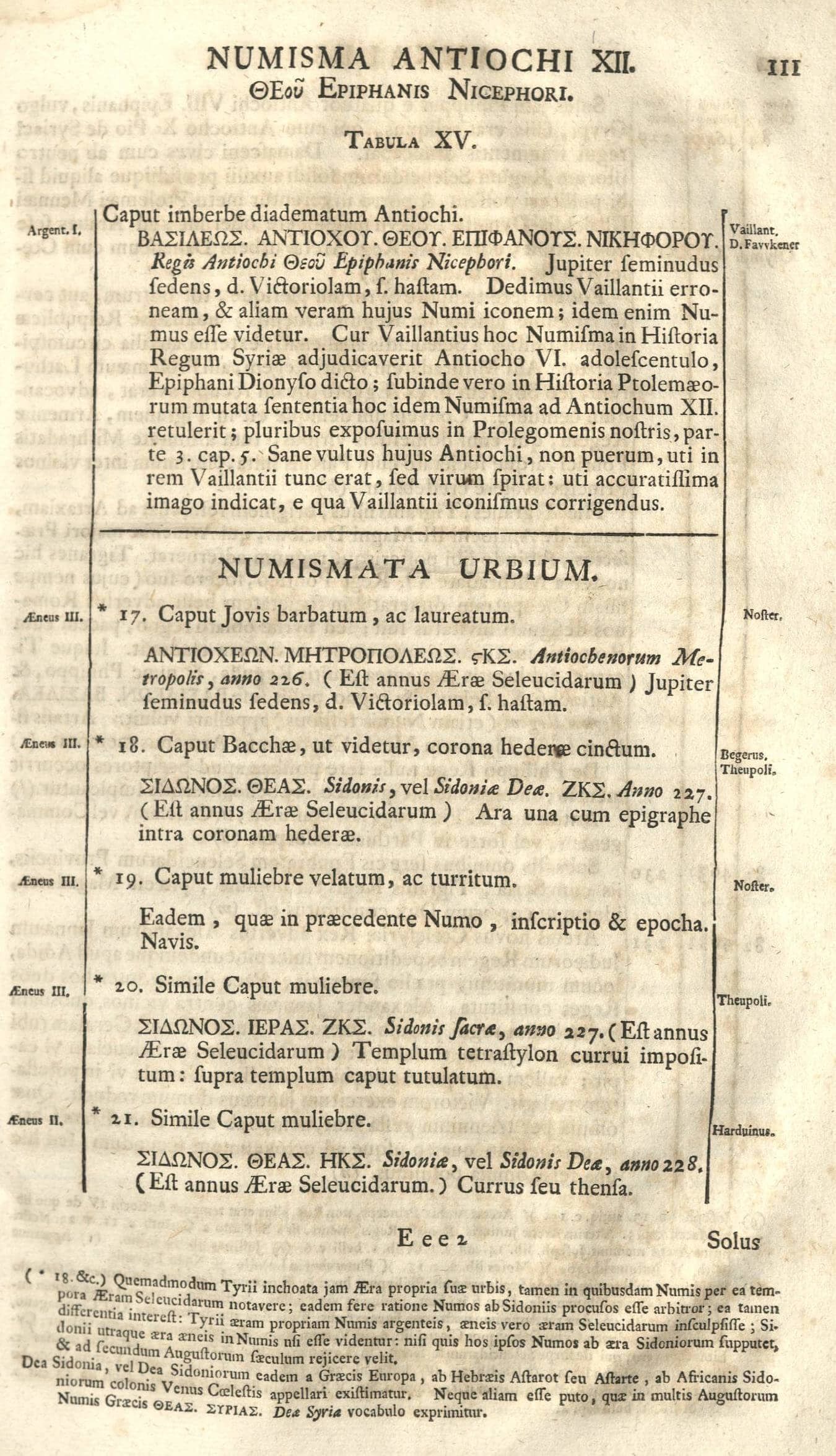

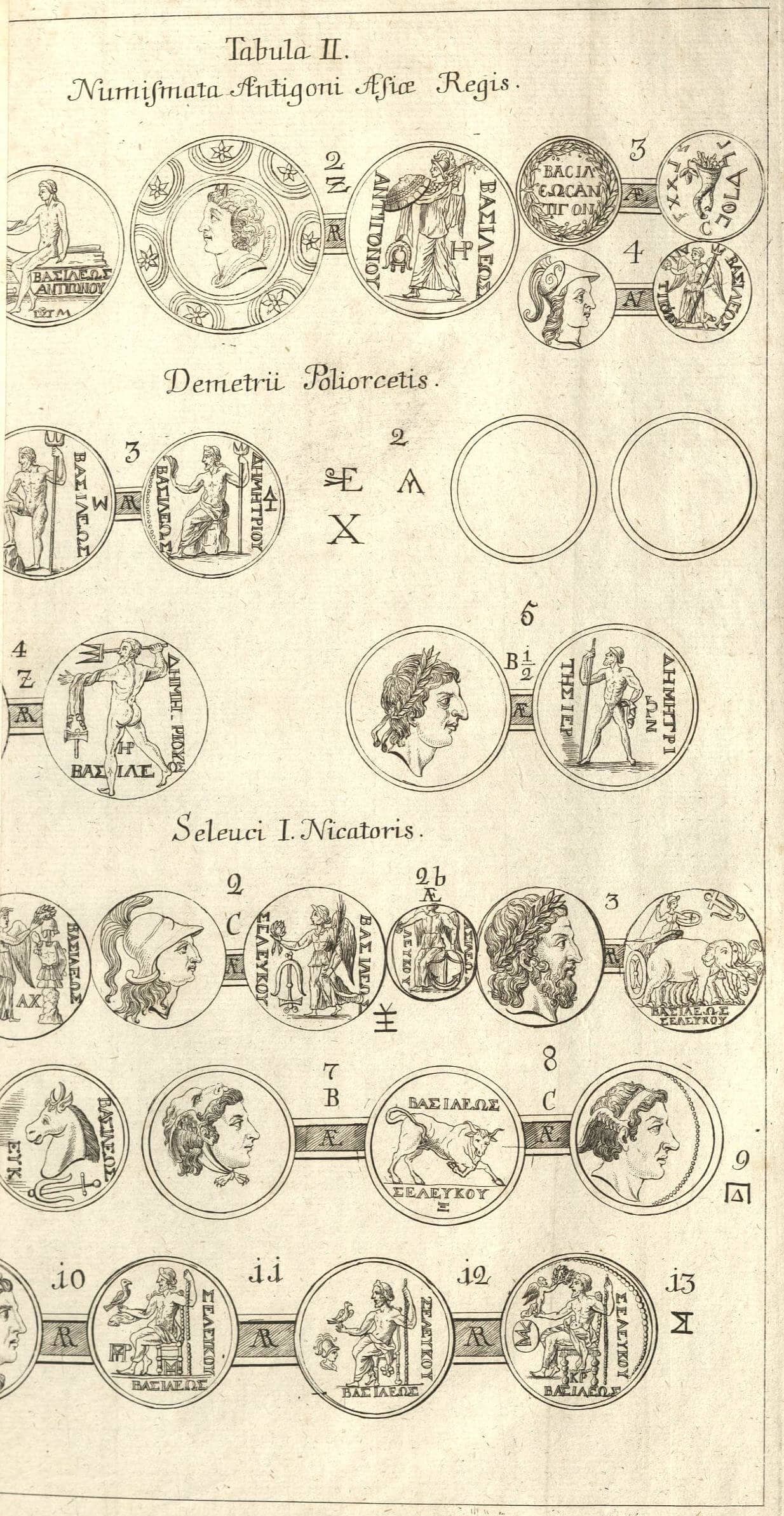

One wonders when Froelich, in addition to his extensive duties, found the time to tackle his opus magnus, his Annals of the Syrian Kings, from the death of Alexander the Great to the arrival of Gnaeus Pompeius in Syria.

It was much more than a catalog of coins or a collection inventory, as we have them from the 18th century in large quantities. Froelich posed a specific question, which he wanted to answer with the help of the coins, namely whether the books of the Maccabees, which were considered apocryphal, were genuine or false.

The four books describe the events of the Maccabean Revolt, when strictly observant Jews rose up against the Syrian king Antiochos IV. They are central to the history of Judaism, since Book 2 establishes one of the most important festivals of the Jewish community, the Hanukkah festival. It dates back to the rededication of the Temple after the troops of Judas Maccabee regained control of Jerusalem. But the warlike conflict does not end there. Books 3 and 4 describe how things continued after that.

The Books of Maccabees are among the many writings on which scholars could not agree whether they were holy word or not.

Coins as a historical source

To this end, Froelich compiled the Annals of the Kings of Syria as the centerpiece of his work. He listed, arranged by years, the events of their history known from literature. On one side are the events, arranged according to the Christian era, according to the Julian calendar enriched with dating according to the Seleucid era and the Olympian reckoning. On the other side are the coins, which thanks to their dating according to the Seleucid era, can all be assigned to a fixed date.

Froelich used the data secured by this comparison to argue that the First and Second Books of Maccabees found in the Catholic biblical text must be historically accurate, genuine, and thus divinely inspired.

Of course, the Catholic world was thrilled! One will be little surprised that the Protestant world, although no one could deny the great scientific achievement behind this work, came to a different conclusion.

Each time writes its own history

For all his scientific brilliance, the numismatist and historian Erasmus Froelich had overlooked the fact that coins and facts can reconstruct facts, but they cannot prove faith. That an event actually took place says nothing about its interpretation.

Questions of faith cannot be discussed on the basis of facts. Otherwise, it would not be a matter of belief, but of knowledge.

A coin collection as a political pledge

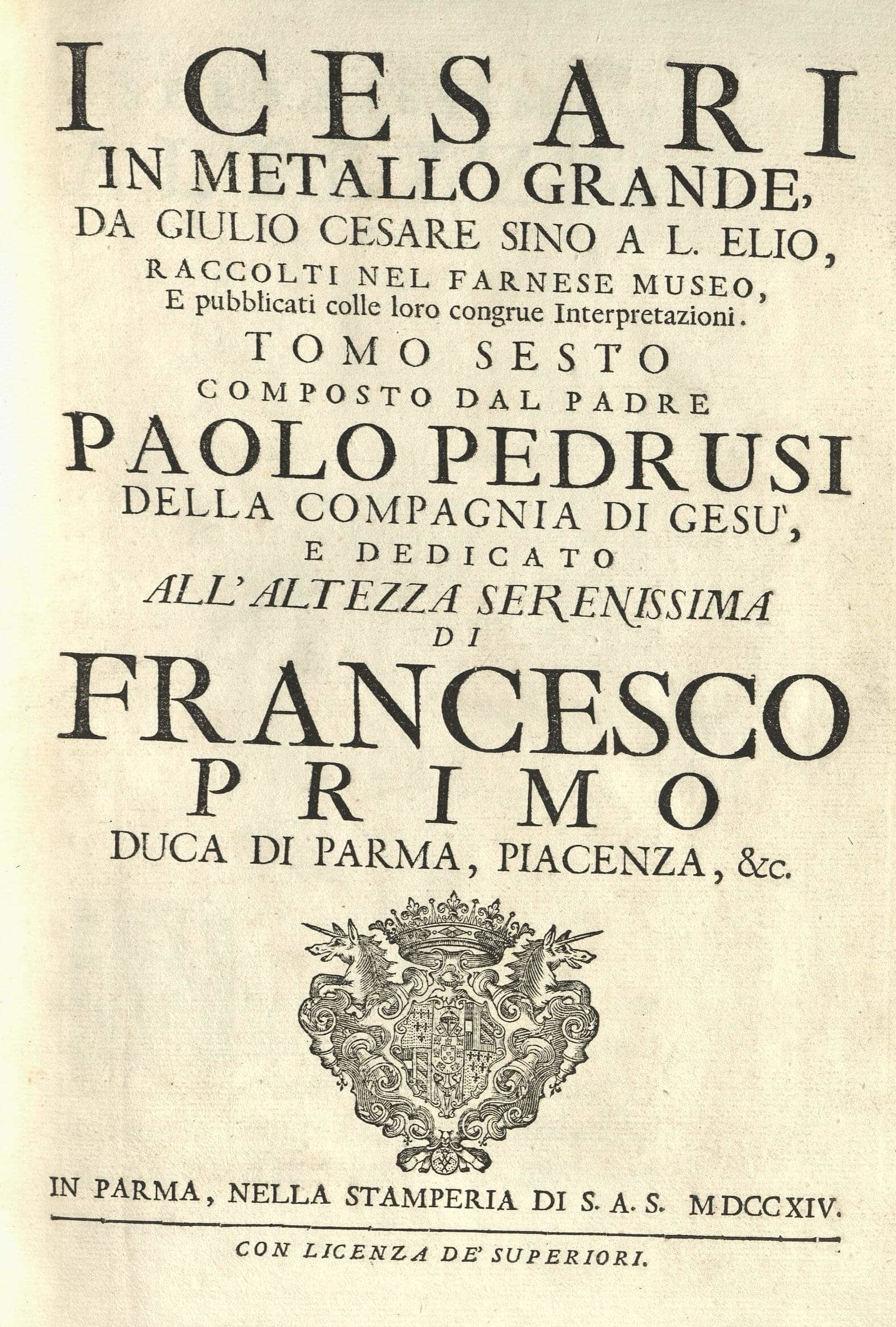

Paolo Pedrusi, I Cesari in Metallo Grande da Giulio Cesare sino a L. Elio, raccolti nel Farnese Museo. Band 6, published in Parma 1714

We do not know much about the Jesuit Paolo Pedrusi (*1644, +1720), the author of this book. The publication of the coin collection of the House of Farnese was his life's work. And yet he himself was not important. He was an interchangeable tool of the duke. Whoever opened the book immediately met the owner of the collection, the Duke of Parma and Piacenza. His name is also written on the title much larger than that of the author.

A powerless prince and his collection

To understand the function that a coin collection had during the late Baroque period, we need only look at the engraving that is bound in our edition opposite the title page. It shows Francesco Farnese, its owner, Duke of Parma and Piacenza. Above him hovers Fama, public opinion, proclaiming his glory with her trumpet. The hanging of the trumpet shows the Roman she-wolf with the two twins, referring to the Roman coins of the publication. On the lower right we see Minerva, whom the Baroque interpreted as a goddess of knowledge. The prince himself stands on the left, erect, in full armor with allonge wig. He places his right hand on the books dedicated to him. In his left hand he holds the laurel wreath of the victor.

But in real life Francesco I was certainly not a victor, quite the contrary. As Duke of Parma and Piacenza, he was a rather mediocre ruler whom the contemporary great powers considered weak and thus vulnerable to attack.

One would now like to believe that a prince like Francesco, who was fighting for the survival of his state in a warlike environment, would have had other things to do than publish his coin collection. But in the Baroque era, an extensive coin collection was something with which one could certainly score points. It testified to the political connections of its owner.

The Farnese Collection

A collection reflected the importance of the collector. The collector - in very few exceptional cases the collector - received the objects only thanks to good connections to educated and powerful men all over Europe. So the reverse was true: Whoever owned an extensive collection had to be a powerful man.

The baroque stage

But it was precisely those who were powerless in the Baroque era who had to pretend to the outside world that their resources were unlimited. Francesco's efforts were not entirely unsuccessful: it was a diplomatic coup when he, the small, impoverished, insignificant prince of Parma, was able to marry off his stepdaughter Elisabetta to the just widowed Spanish king Philip V in 1714. Thanks in part to the collection, the Duchy of Parma was considered desirable, and it was understood that Francesco's wife, already 44 years old in 1714, would not bear any more children. This meant that - apart from an unmarried brother - there were no official heirs, so Philip V knew that the Duchy of Parma would fall with the collection to his and Elisabetta's son. But this deal also had a clear advantage for Francesco: as long as he lived, Spain protected his duchy!

The move of the collection

After that, however, the collection was taken away. Charles took it to his kingdom of Naples and Sicily. There it is still today in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples. The statues are in the countless halls of the museum. The coin collection, on the other hand, is located in the - mostly closed - mezzanine. A sad fate for this collection, which was also so important politically at the time, and which was so lovingly and lavishly published by Paolo Pedrusi.

Paolo Pedrusi's book testifies to the fact that for many centuries numismatics was much more than a science. It was a field in which rulers competed. Whoever made it far in this field was also considered politically influential. And in this way, many a prince was able to cover up the fact that his empire had long since passed its zenith.

Coin collection as a prestige object

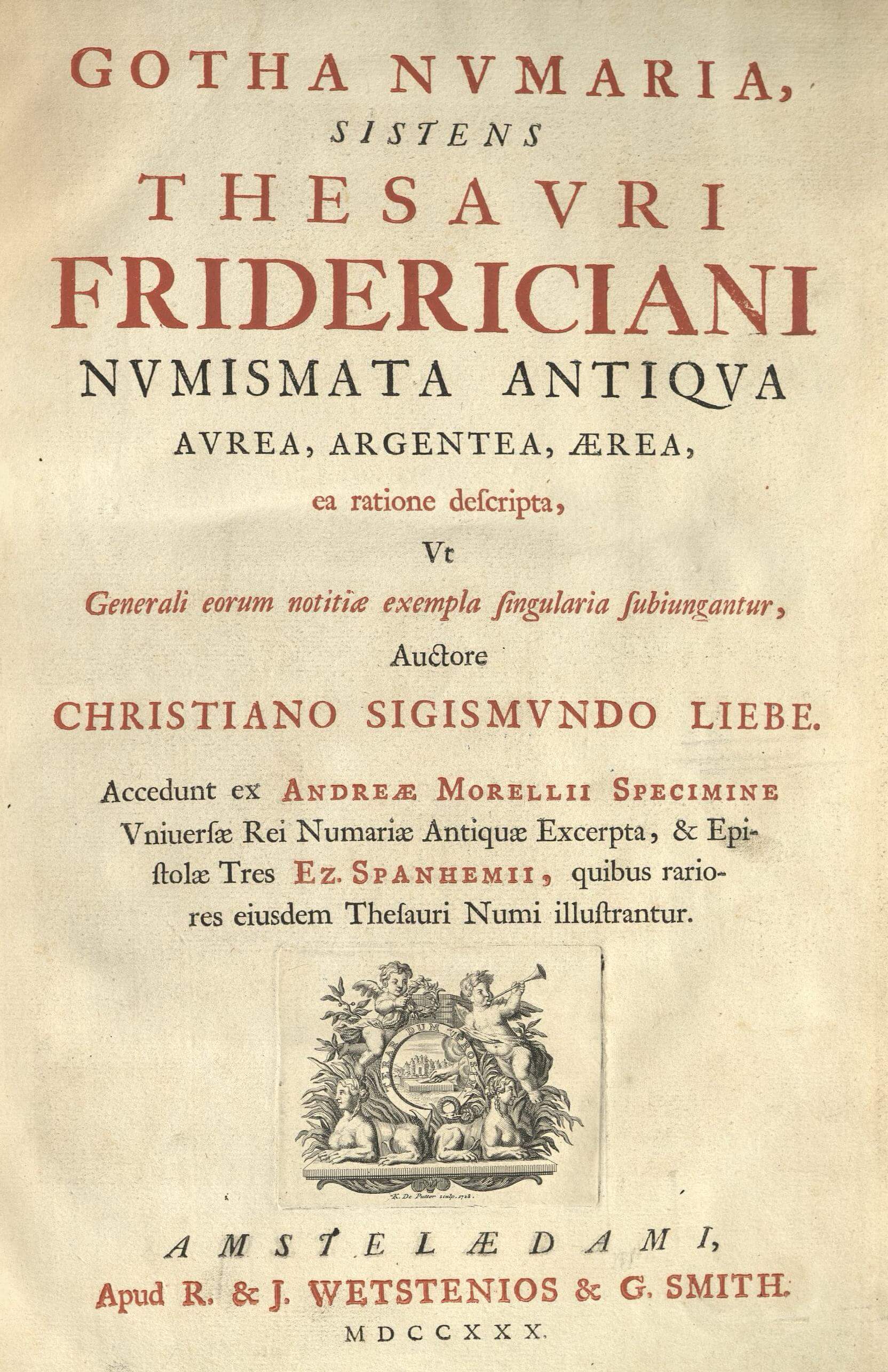

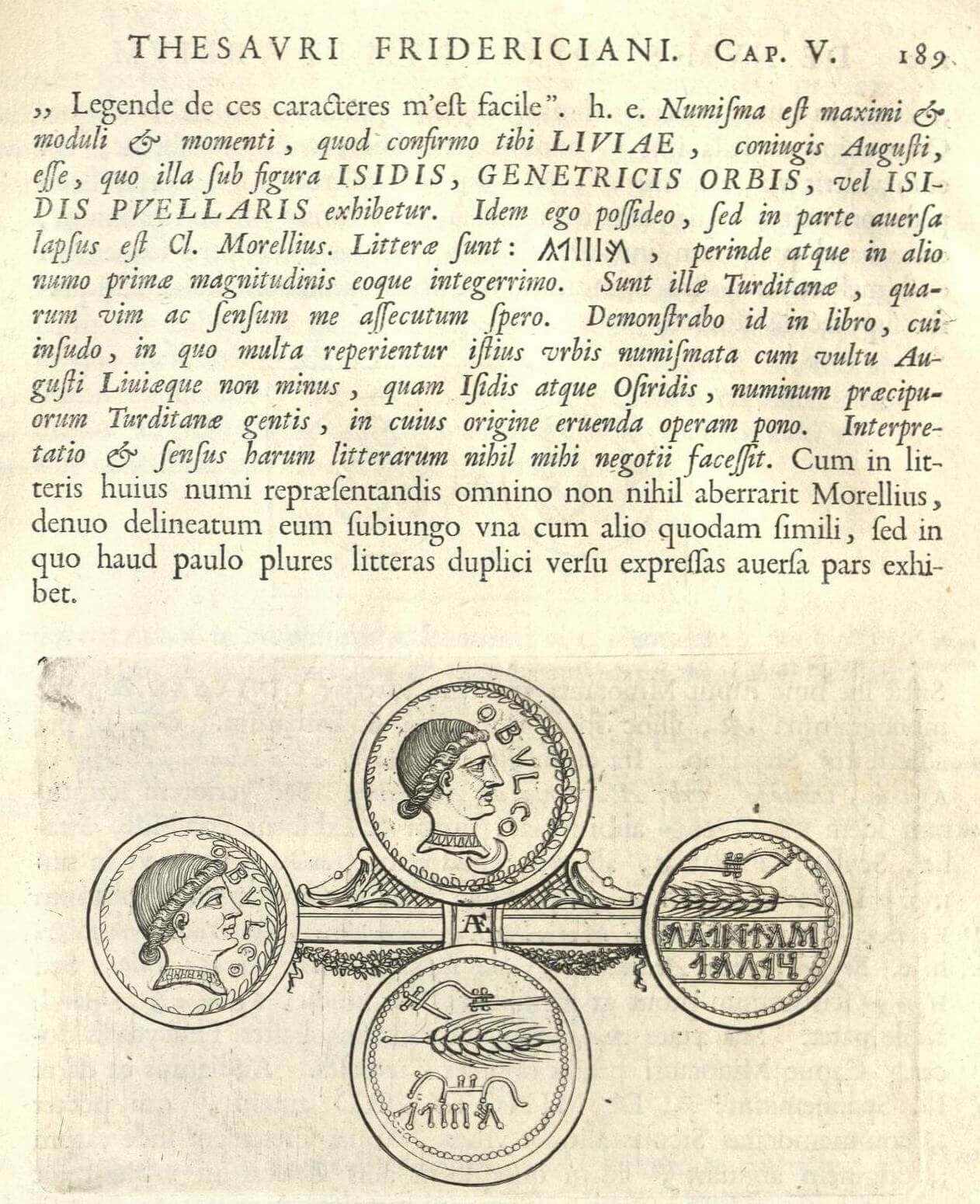

Christian Sigismund Liebe, Gotha numaria, sistens thesauri Fridericiani numismata antiqua aurea, argentea, aerea ea ratione descripta. published in Amsterdam, 1730

Friedrich II. von Sachsen-Gotha-Altenburg

Friedrich II. von Sachsen-Gotha-Altenburg

What do you do when you have ambitions but your own resources cannot keep up with the demands? Frederick II of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg acquired the famous coin collection of Count Anton Günther II of Schwarzburg-Sondershausen zu Arnstadt in 1712.

He had a representative room built where visitors could admire the treasure. He commissioned the publication of the collection. Naturally, Latin was chosen as the language for the book. Finally, all scholars at home and abroad could read what treasures were to be found in Gotha.

From then on, Gotha was an international center for all friends of numismatics, and there were many of them among the high nobility, because like golf, dressage riding or sailing today, numismatics was considered the noblest occupation worthy of a ruler at that time.