Knowledge

for all

Enlightenment revolution

The first Swiss encyclopedia, 1747-1795

by Johann Jakob Leu, mayor of Zurich and founder of what was to become Bank Leu.

A new age has dawned, the age of enlightenment.

Everything will be brighter, better and more beautiful than it was in the dark Middle Ages under the rule of the nobility and clergy. This may have been the thinking of the intellectuals who had set out to cut off the old braids of the nobility. Education was their means of choice to defeat the autocracy. Knowledge - beyond God and the creation myths - was supposed to make the world a comprehensible place.

This knowledge could not be limited to a ruling elite, but had to be available to everyone. After all, the liberals were convinced, the knowledge in people's heads would initiate the revolution in autocratic states. Whereby the term "man" at that time was quite naturally - even the most progressive Enlightenment thinkers were, after all, children of their time - limited to white men.

The heyday of encyclopedias

To organize knowledge in an easily accessible way, authors used the medium of an encyclopedia or dictionary. Unlike a simple dictionary, an encyclopedia presented not only the translation of a term, but detailed factual information. Thus, anyone who wanted to obtain basic information about a subject found everything he needed in such an encyclopedia. A clear order of the terms according to the alphabet made it a breeze to get to the knowledge.

Thus, encyclopedias developed into international bestsellers. They offered citizens, who had spent their time more on acquiring money than knowledge, the opportunity to subsequently acquire the knowledge they needed to keep up in learned societies and salons.

Probably the most famous encyclopedia project of this time is the famous Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot.

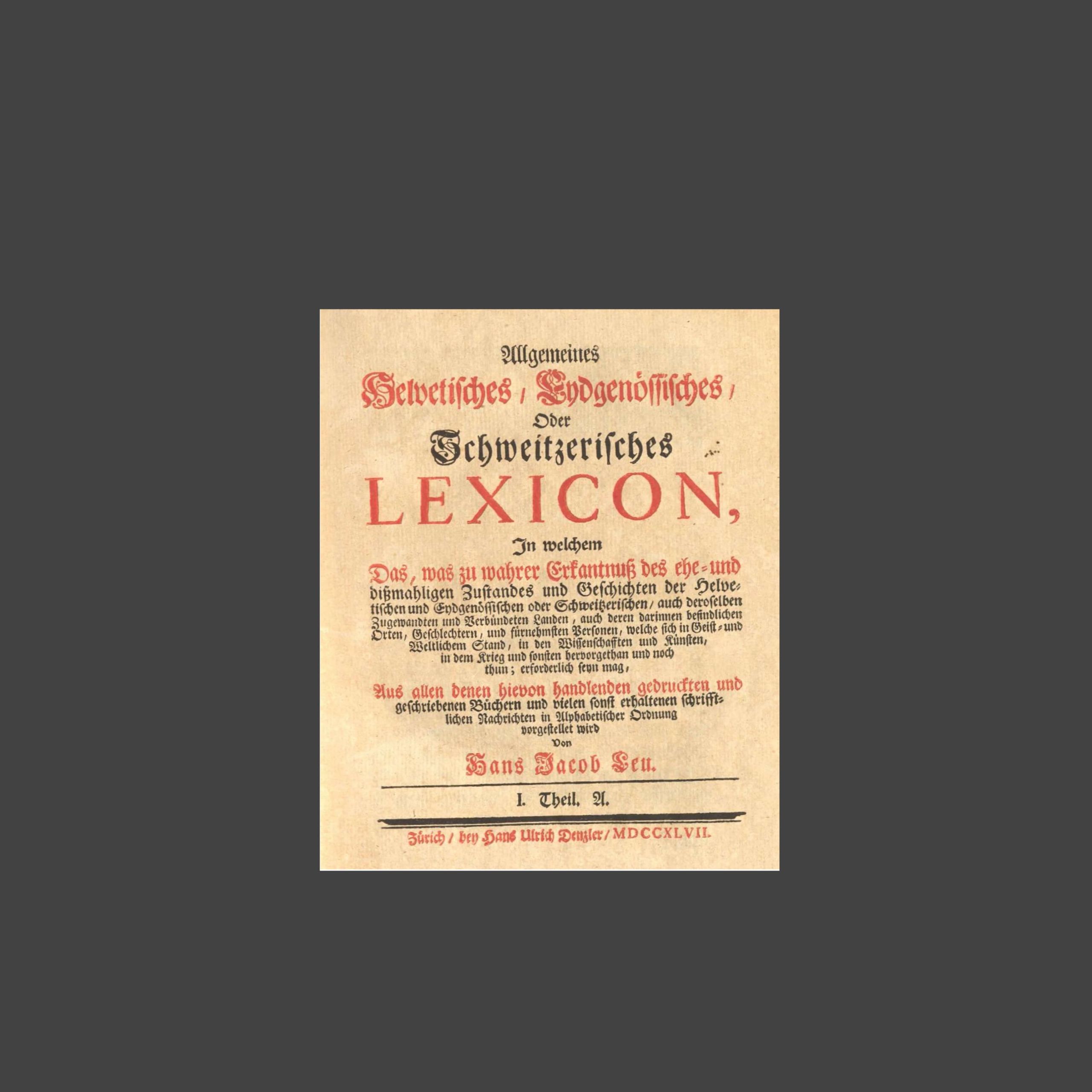

The first volume of the example we are presenting here, namely the "Eidgenössisches Lexikon" published by Johann Jakob Leu, was published in 1747 - already five years before the first volume of the Encyclopédie. And at that time, the Eidgenössisches Lexikon was already part of a long tradition. Thus, the most famous and comprehensive German encyclopedia, the "Zedler" with its 63,000 pages in 64 volumes with 284,000 entries, was already almost complete. And these are only three examples of many.

The middle of the 18th century was the heyday of encyclopedias. Encyclopedias were good business for publishers. For example, a well-known Leipzig publisher listed as many as 20 different encyclopedias and dictionaries in its catalog for the year 1741.

Encyclopédie by Denis Diderot.

Encyclopédie by Denis Diderot.

Swiss Encyclopedia by Johann Jakob Leu

Swiss Encyclopedia by Johann Jakob Leu

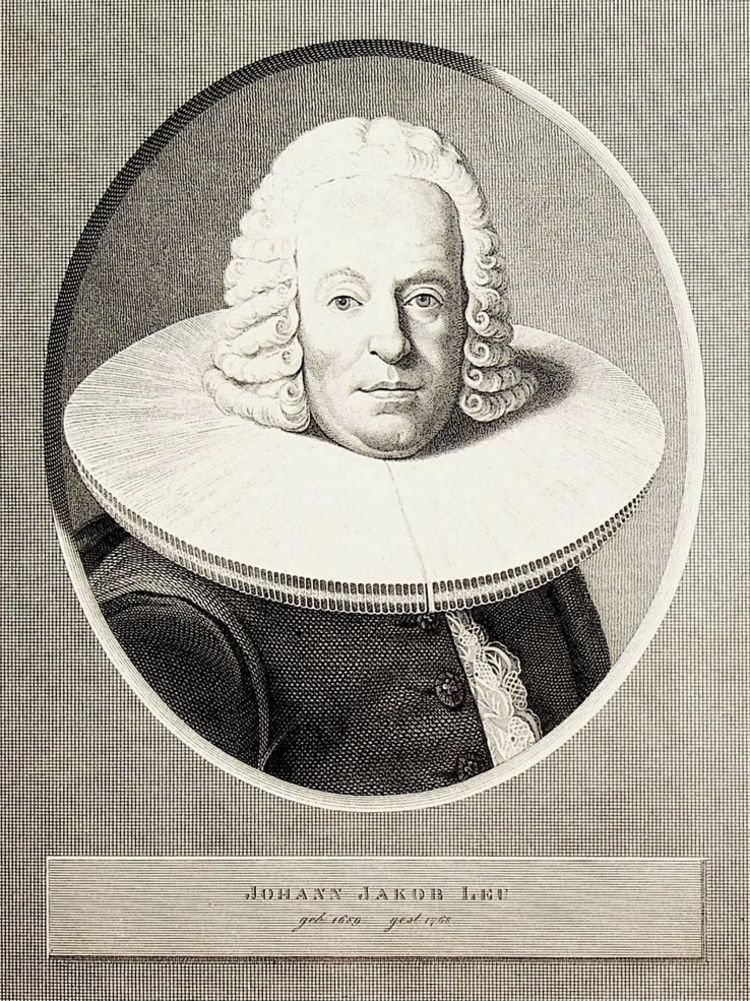

Johann Jakob Leu in Zurich

But the man who wrote the Eingenössisches Lexikon was not in it for the business. While commercially attractive projects such as the Zedler or the Encyclopédie were financed through subscriptions, Johann Jakob Leu paid for both the research and the printing of the most important Swiss encyclopedia of the early modern period out of his own pocket.

So who was the man who began and, above all, completed such a comprehensive project? And what spiritual background inspired him to undertake it?

Johann Jakob Leu was born in 1689 as the son of a politically and economically influential Zurich family. Zurich was experiencing an economic boom at the time. It had emerged more or less unscathed from the Thirty Years' War, which had hit many cities in the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation hard. The Toggenburg War had further strengthened Zurich's position as a Reformed trading city in the Confederation. The available capital, high returns, safe trade routes and low taxes offered Zurich merchants incentive and opportunities in abundance to accumulate large fortunes.

Zürich

Moreover, wealthy Zurich was known throughout Europe as an intellectual center where progressive minds discussed and published uninfluenced by church or state censorship. This naturally attracted many independent thinkers. The German poet Wilhelm Heise marveled at the fact that of the city's then population of about 10,000, some 800 had already published. In the 18th century - when it was much more expensive and elitist to produce a book - an incredible number.

Another figure is just as significant: around 1750, more than 60% of the population in two-thirds of Zurich's parishes were already able to read. Consider, for example, that in the Habsburg monarchy Maria Theresa did not introduce compulsory education until 1774! So there were many people in Zurich who could also read the written books. And so Zurich's book trade boomed. The city had five major publishing houses with attached printing works, fifteen publishing bookstores and 27 smaller bookstores.

At least as important were the private salons and even more so the learned societies, where Zurich citizens and invited guests from abroad discussed the latest trends in philosophy, historical research and the natural sciences. There were thirty such societies in Zurich alone. The star of Zurich's learned world was the internationally renowned philologist Johann Jakob Bodmer, a contemporary of Johann Jakob Leu. He owed his fame to the translation of Homer.

Zurich from the lake.

Copper engraving by Merian, 1650.

Zurich from the west, copperplate engraving by Merian, 1650.

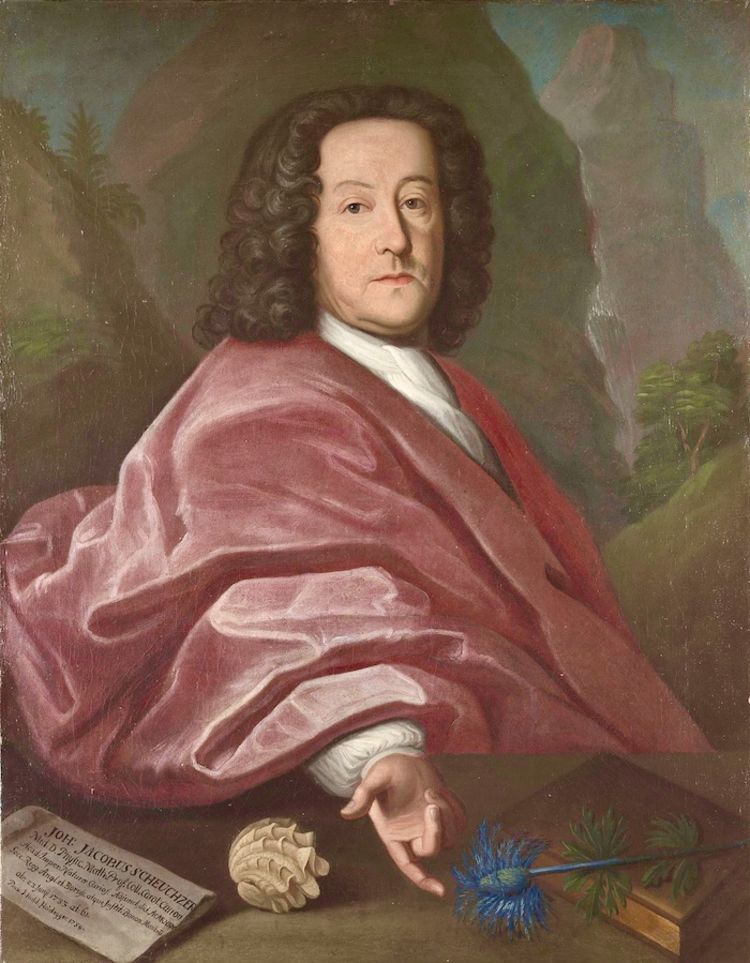

Leu's teacher was a natural scientist: Johann Jakob Scheuchzer, founder of paleobotany and known to us mainly for his Flood theory. He interpreted the fossils as the remains of creatures that had perished in the Flood. What elicits more of a smirk from us today was a hotly debated theory in Leu's day, prompting Tsar Peter the Great's attempt to lure Scheuchzer to St. Petersburg with a high-paying position.

Leu's career

Even the young Johann Jakob Leu was offered a stimulating environment, which inspired the 15-year-old to write a comprehensive biography of the Zurich antist Johann Jakob Breitinger. This was not to remain his only work. Leu wrote many important books. His decision to write an encyclopedia containing everything there was to know about the Swiss Confederation is said to have been made at the youthful age of 17. He did so after meeting the aged Basel historian and lexicographer Johann Jakob Hofmann, whose encyclopedia was little used. Hofmann had made the mistake of writing it in Latin. At that time, only a small part of the educated elite knew Latin. Leu was to do better.

But we got a little ahead of ourselves with that. First, Johann Jakob Leu studied both laws, which in the early modern era was a basic prerequisite for entry into the higher civil service. He earned his doctorate, visited the capitals of Protestant Europe as part of his Grand Tour, and then joined the civil service in Zurich.

We do not need to list all the stages of Johann Jakob Leu's career here. Suffice it to say that he was talented and hardworking, and his fellow citizens rewarded his achievements with increasingly high positions. In 1749 he became Seckelmeister, an office that was a cross between Minister of Finance and President of the National Bank. For although we can only deal with Leu's most important initiative in passing here, it is worth mentioning that our encyclopedia writer was a co-initiator and the first president of the famous Zurich Interest Commission, which we know as Bank Leu. Although this institution was state-owned, it operated independently of the city's financial administration. It offered public and private investors in Zurich the opportunity to invest their money profitably. From 1755 onwards, the managing directors brokered Zurich capital to creditworthy states and entrepreneurs abroad.In 1759, Johann Jakob Leu crowned his career by being elected mayor.

By this time, the busy man had already published his most important books. These included not only the aforementioned biography, but also legal works, such as a comprehensively annotated new edition of Simmler's Federal Constitutional Law and a four-volume compendium of Swiss private law. These books remained standard works for decades and were excellent preparation for the Federal Encyclopedia.

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer, the teacher of Leu.

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer, the teacher of Leu.

Johann Jakob Leu

Johann Jakob Leu

The Federal Encyclopedia

In the years between 1747 and 1765, Leu published the first encyclopedia devoted exclusively to Switzerland, which was completed to the last volume. It comprised 20 volumes in quarto format. They represented on 11,368 pages in (estimated) 20,000 keywords everything that could be found in terms of information about Switzerland. It is thus the largest and most complete encyclopedia published on the Swiss Confederation in the early modern period.

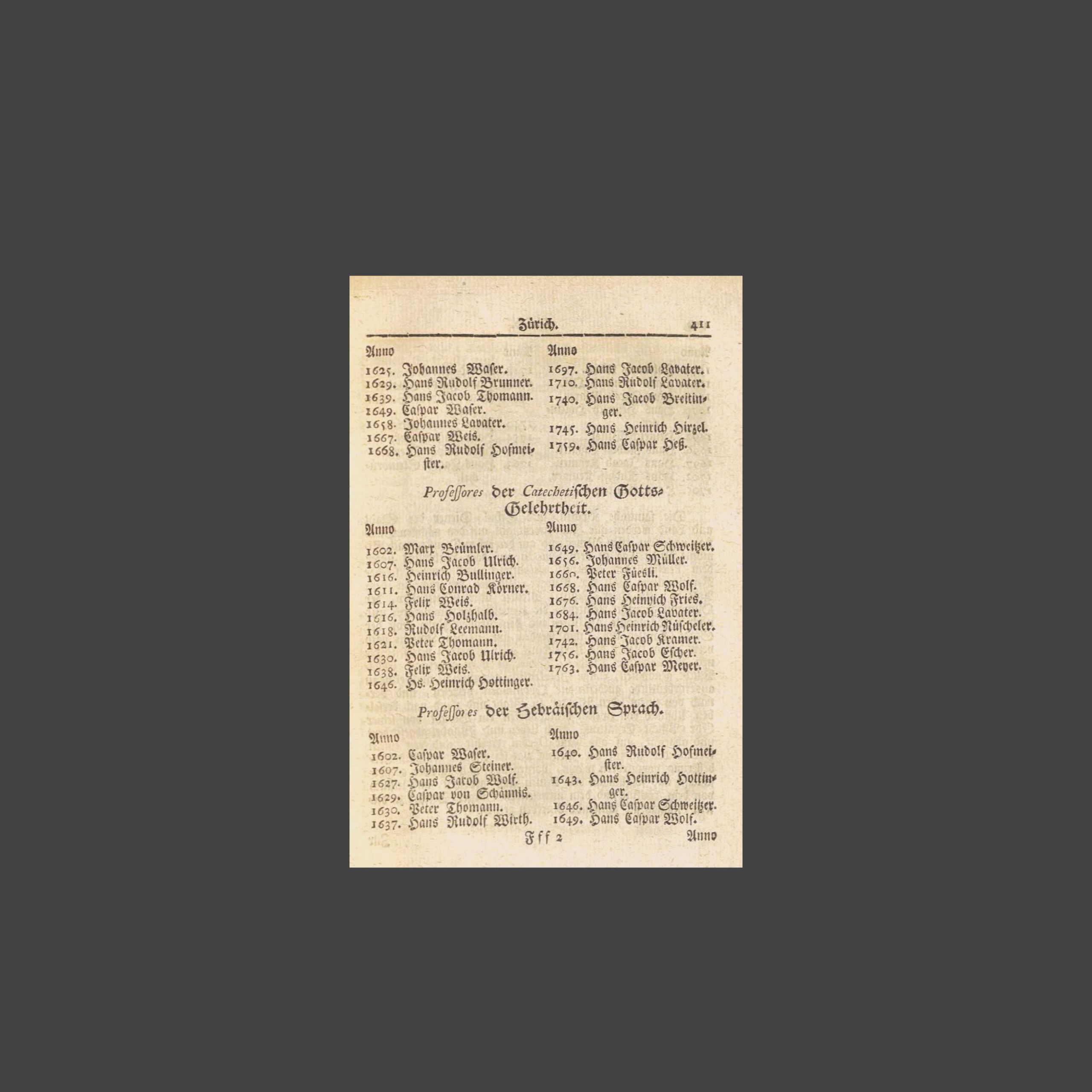

In the Federal Encyclopedia the reader found a wealth of information: Biographies of important personalities and genealogies of the most important families. Swiss and related places, abbeys, monasteries, mountains, valleys, lakes and spas were listed as well as legal and political terms. Leu provides information on history, on well-known Swiss products, on trade and on folk customs.The quality of the information can of course be debated. Some authors accuse Leu of being more efficient than perfectionist, more of a collector than an independent researcher. One may well ask whether this is still an accusation that has any validity outside the academic world in our time.

Of course, an individual who published such a comprehensive work had to rely on others for information. And thus no article was better than the material available to Leu. He was able to draw a great deal from the rich collection of books in Zurich's civic library. Here he sat at the source, since he had been its librarian since 1710 and its president since 1758. In addition, Leu collected a lot of material during his travels, which he often undertook on behalf of the city of Zurich. Leu's work is particularly useful because of the many verbatim copies of documents that no longer exist today and because of the detailed lists of names of office holders.

The Swiss Lexicon transmits these sources to us with a reliability and objectivity that make it a valuable, if not in some cases the only source for historians.

Leu's genealogical articles are problematic. For their content, he resorted to what members of the families concerned sent him. And this was, of course, anything but objective, but an embellished version that Leu adopted mostly unchecked, but often abridged. And it was precisely these genealogies that earned Leu the most criticism among his contemporaries. They were the most important to the potential clientele, which was recruited from the councilable Swiss families. And that is where the readers reacted very emotionally. After all, who wanted to have an encyclopedia in their house that gave more space to the competing family than to their own, or even passed over their own family with silence!

It was not until the nationally minded historians of the 19th century that Johann Jakob Leu's work was appreciated in its full significance. After all, it was the most important reference work on old Switzerland for over a century. Today, we stand in awe of this encyclopedia created by a man whose achievements would have been enough for three biographies. He rose to the highest state office in his homeland. He was substantially involved in the founding of a financial institution that flourished for more than 200 years. And he created an encyclopedia that remained unrivaled for a century and is still used by historians today.

Leu's work is particularly useful because of the many verbatim transcriptions of charters that no longer survive us today, as well as the detailed lists of names of office holders.