How Zurich became a

Money City

"city air makes you free"

Zurich is situated in a privileged geographical location. Where Lake Zurich flows into the River Limmat, a trading center developed as early as Celtic times on the north-south connection between Upper Italy and Lake Constance. Today's cosmopolitan city of Zurich began very small.

The 13th century: free of empire

In 1218, the last feudal lord of Zurich, Duke Berthold V of Zähringen, died. Thus the rights over the city of Zurich - taxation and jurisdiction, to name but two - reverted to the emperor. Frederick II needed money at the time, and so the citizens of Zurich succeeded in obtaining imperial immediacy from him. The approximately 5,000 citizens of Zurich who lived in the city at the time were thus given the opportunity to organize themselves.

In the scramble for power and influence, the burghers increasingly prevailed in the course of the 13th century, as they had the means to buy the most important privileges such as market and minting rights from the abbess of the Fraumünster.

Around 1300, Zurich was one of the most important market towns in Upper Germany with excellent connections to Upper Italy and to the trading cities on the Lower Rhine.

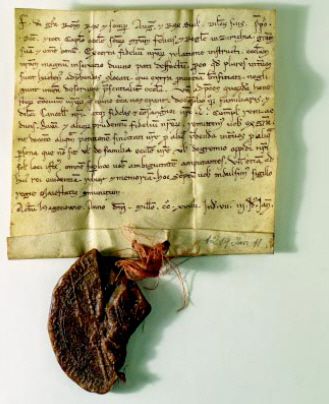

In 1219 Frederick II granted the city of Zurich imperial immediacy. "Every person who comes to this place and wants to stay there shall sit and stay freely." This is how Frederick II's city charter privilege of 1218 reads for the city of Berne. And in other cities, similar procedures were similarly followed.

In 1219 Frederick II granted the city of Zurich imperial immediacy. "Every person who comes to this place and wants to stay there shall sit and stay freely." This is how Frederick II's city charter privilege of 1218 reads for the city of Berne. And in other cities, similar procedures were similarly followed.

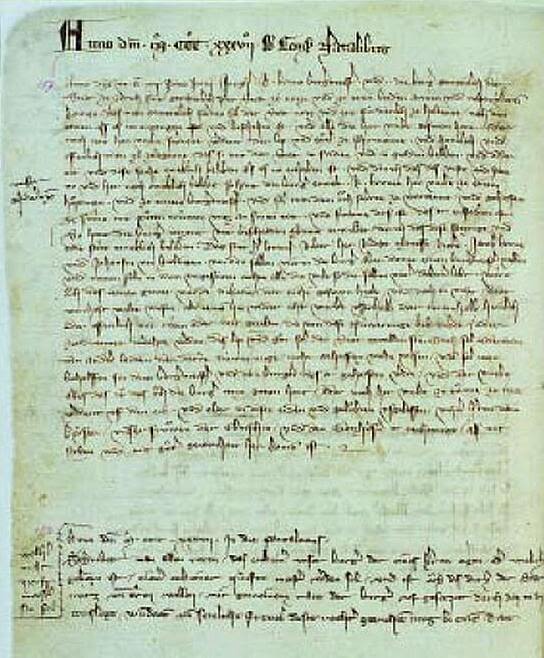

Entry from the Zurich City Book of 7 June 1336 about the future election of the mayor.

Entry from the Zurich City Book of 7 June 1336 about the future election of the mayor.

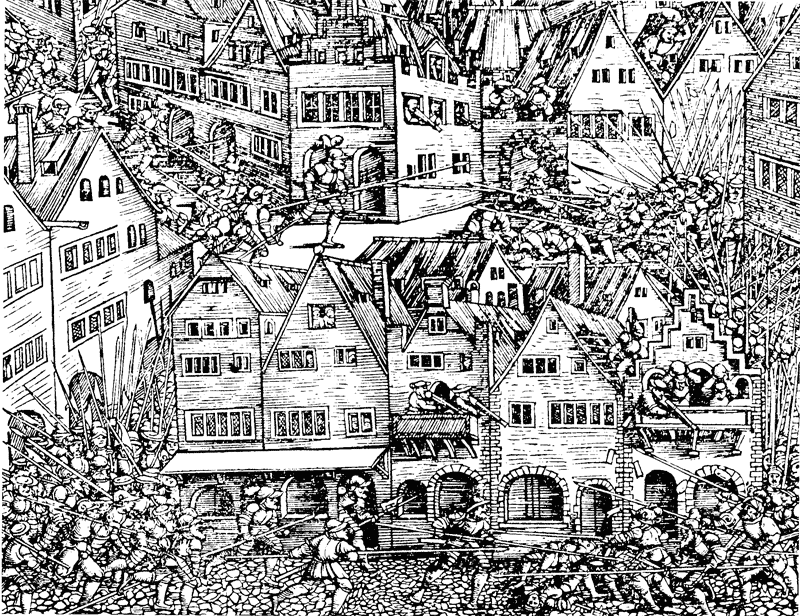

The people of Zurich defend their constitution in the Zurich Murder Night of 1350. Illustration from the chronicle of Johannes Stumpf.

The people of Zurich defend their constitution in the Zurich Murder Night of 1350. Illustration from the chronicle of Johannes Stumpf.

The 14th century: Commerce takes power

At the beginning of the 14th century, Zurich's citizenry was made up of nobles, merchants and craftsmen, all of whom represented different interests. While the merchants were interested in securing trade routes, the craftsmen advocated expansion into neighboring territories in order to gain control over their raw materials and sales markets - signs of the emerging money economy.

In the course of the 14th century, the merchants pushed the nobility out of political office, while the craftsmen's guilds, which had no influence in the council, simultaneously grew in importance. It came to an open fight in 1336, when the craftsmen with their guilds overthrew the government.

Brun's guild constitution stipulated that in the future 13 noblemen and patricians, together with the 13 guild elders, were to run the fortunes of the city. In a modified form, this constitution remained in force until 1798.

The merchants thus lost their political dominance, and this had an impact on the development of the city. Zurich concentrated on urban crafts. The city on the Limmat neglected long-distance trade and developed into a market center for the surrounding communities.

Holy Roman Empire, Fraumünster Abbey Zurich, Elisabeth von Wetzikon, penny end of 13th century

Until the Reformation of 1524, the abbess of the Fraumünster was the city ruler in Zurich. As such, she held the right to mint coins and had pennies struck. On the early coins, the city saints were predominantly depicted. On later mintings, the respective abbesses had their own portraits set. This bracteate shows a schematic picture of Abbess Elisabeth of Wetzikon (1270-1298).

Until the Reformation of 1524, the abbess of the Fraumünster was the city ruler in Zurich. As such, she held the right to mint coins and had pennies struck. On the early coins, the city saints were predominantly depicted. On later mintings, the respective abbesses had their own portraits set. This bracteate shows a schematic picture of Abbess Elisabeth of Wetzikon (1270-1298).

Zurich's coinage in the late Middle Ages is still modest, and the coins are often minted only on one side.

Holy Roman Empire, City of Zurich, Heller

The Heller, which was called Haller in Zurich, was used as a divisional coin. This is a nominal of only small value, which is used to settle small differences in transactions. To keep the cost of these small coins as low as possible, they were minted only on one side. The Heller shown here bears the Zurich coat of arms as a die.

The Heller, which was called Haller in Zurich, was used as a divisional coin. This is a nominal of only small value, which is used to settle small differences in transactions. To keep the cost of these small coins as low as possible, they were minted only on one side. The Heller shown here bears the Zurich coat of arms as a die.

The 15th century: Expansion

By concentrating on local trade, it became existential for Zurich to have as extensive a surrounding area as possible. The expansion drive of a money economy. This political goal was pursued by legal means, force and the use of money . The surrounding countryside guaranteed the supply of wine, grain and meat to the city as well as the sale of goods produced in Zurich - all at the prices set by the Zurich council.

In 1433, Emperor Sigismund granted the citizens of Zurich the right to make their own laws for themselves and their subjects. The citizens of Zurich took advantage of this privilege by attempting to monopolize craft production for the city, while the inhabitants of the countryside were confined to the production of agricultural products.

In terms of territorial conquests, the council acted successfully. It acquired the property of indebted nobles and waged war when the opportunity presented itself. The Old Zurich War over the Toggenburg inheritance belongs in this context, as does the annexation of Winterthur in 1467, Stein am Rhein in 1459/84 and Eglisau in 1496.

The territorial development of the city-state of Zurich. Image: wikipedia, Marco Zanoli.

The territorial development of the city-state of Zurich. Image: wikipedia, Marco Zanoli.

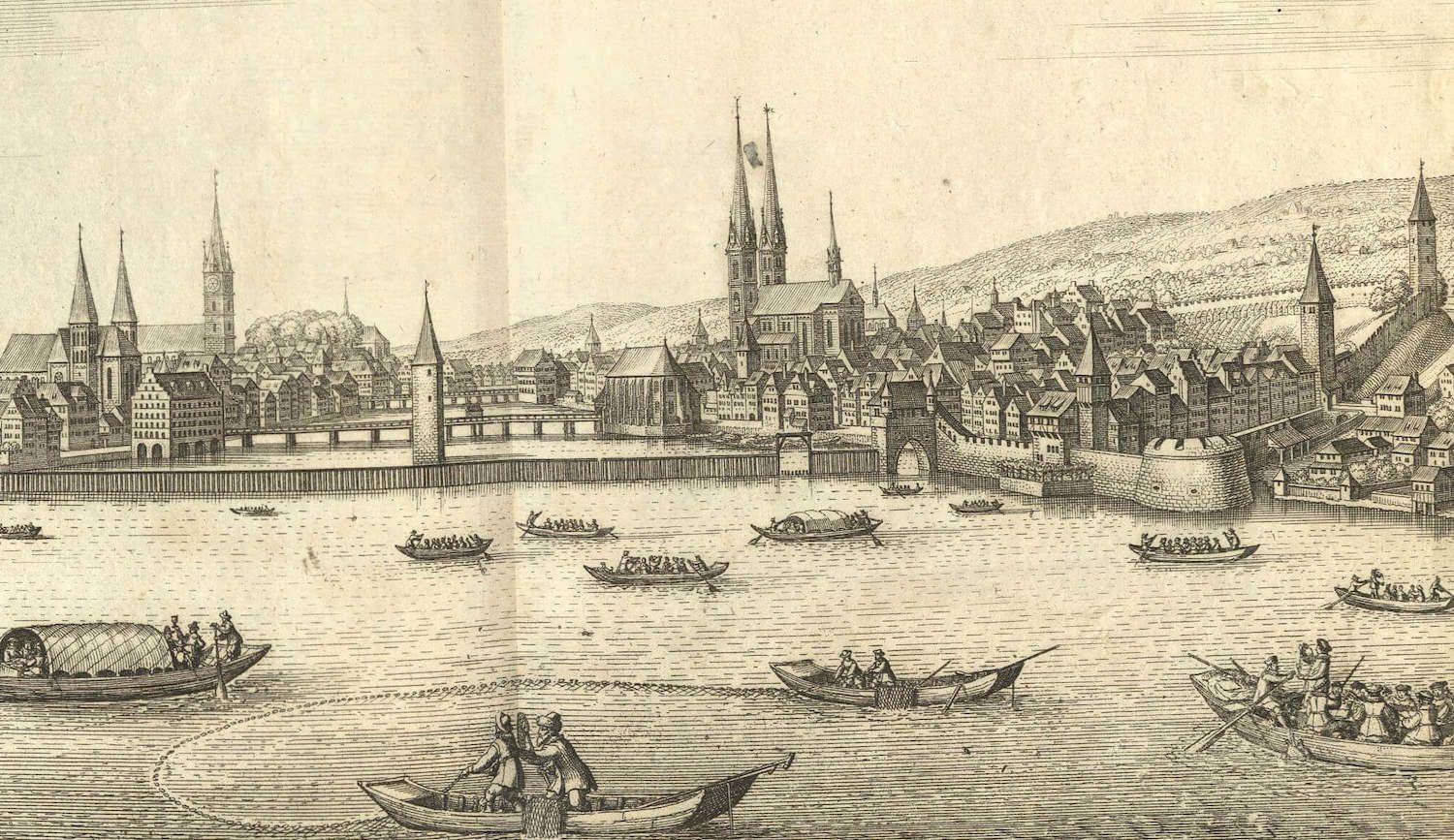

Murer map of Zurich from 1566.

Well recognizable are:

1. The convenient location on the river.

2. the oversized city wall from the 13th century, which left room for several monasteries: the Dominican Preacher Monastery, the Franciscan Barfüsser Monastery, the Augustinian Monastery, the Benedictine Fraumünster and the Dominican Oetenbach Monastery.

3. These were incorporated into the state during the Reformation, i.e. secularized. A truly good business, economically speaking!

Zurich today

How did the transition from the Middle Ages to modern times take place in concrete terms?

Society in the Middle Ages

In the late Middle Ages, i.e. from 1250 onward, a dissolution of the feudal economic and social system sets in. A tremendous upheaval in all areas of life, which reaches a climax in the 16th century.

In the 14th and especially 15th centuries, more and more people flocked to the city, freeing themselves from serfdom. Hence the saying: city air makes you free. For the newcomers, new quarters were built within the city walls, the so-called New Town. As day laborers, however, they no longer have subsistence farming, they can no longer grow their own food, but as professionals they are dependent on their product being bought. Or as employees, they are dependent on someone hiring them.

Money and with it the idea of value and equivalence come about exclusively where a whole community no longer deals only peripherally with buying and selling, but lives from buying and selling. Only such a society depends on the continuous use of a medium of exchange and on its constant circulation.

Society in modern times

From 1500 on, we speak of modern times, probably because the new type of dependencies was the dominant new thing. Since that time money is not only a means of exchange, money is pure means of exchange. Money no longer consists in something that can be exchanged among others, but consists in nothing but that it can be exchanged for something. Money must continue to be exchanged for goods in order to remain money at all. This is the reason for the growth pressure, the dual nature of which Goethe described so beautifully and clearly in his Faust II.

Anyone interested in precisely this phase, this great upheaval, should read Eske Bockelmann's book: Das Geld. What it is that rules us. The second part, How Money Became, reads easily, goes into the term New Town which can be found everywhere in Europe, and describes the new kind of dependence. Here a short introduction.

This new economy and modern money had and still have a strong influence on our society design. In this video, Eske Bockelmann discusses the society of the modern age.

But we're not there yet - we'll follow further developments in the 16th century below.

The 16th century: Reformation and takeover of the monasteries

While the Zurich council promoted the interests of the craftsmen, many nobles had no choice but to earn their living as mercenaries - with all the negative effects on urban tranquility that returned soldiers could cause.

The council reacted by appointing Huldrych Zwingli, known as an eloquent critic of mercenaryism, as a lieutenant priest at the Grossmünster in 1519.

Zwingli was an original theologian who, like many of his contemporaries, criticized the Catholic Church on fundamental issues and called for a break from Rome. The council supported his ideas, mainly because they could only increase his power and influence: Zwingli advocated making the state the guarantor of the moral and religious order of the polity.

In 1520, the Reformation was introduced in Zurich. In 1529, the agreement with Martin Luther failed. Zurich was thus one of the Reformed cities that advocated its own, more radical version of the Protestant faith.

It succeeded in enforcing the Reformation throughout the entire Zurich city area and securing it against the outside world. Due to the great financial resources that a confiscation of the entire former monastery property brought to the Zurich city council, Zurich developed in the long run into the protective power of the Reformed faithful in Switzerland.

Ulrich Zwingli

Ulrich Zwingli

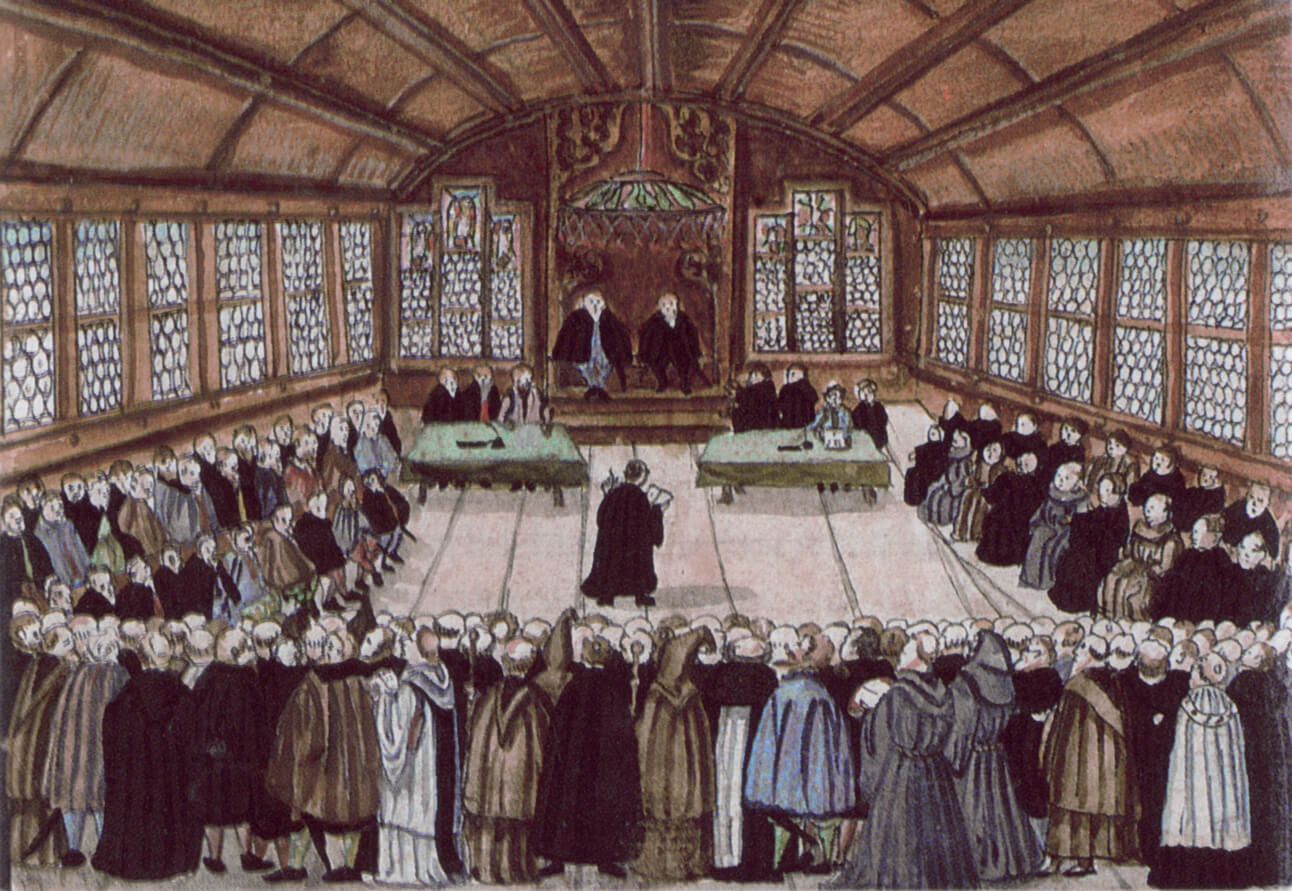

Zürcher Disputation 1523

Zürcher Disputation 1523

Holy Roman Empire, City of Zurich, Groschen 1563. This coin can be minted by visitors to the MoneyMuseum.

Until 1648, Zurich - as shown by the imperial eagle on the reverse of this coin - formally belonged to the Holy Roman Empire. For this reason, the city adhered to the provisions of the coinage regulations issued at the Imperial Diet of Augsburg in 1559 when minting its coins. According to these, the obverse should show the origin of the money, which was expressed here by the Zurich shield. For this purpose, the reverse of the coins had to show the imperial eagle and the denomination. The eagle bears a 3 on its breast, this was a 3 kreuzer coin, a so-called groschen.

Until 1648, Zurich - as shown by the imperial eagle on the reverse of this coin - formally belonged to the Holy Roman Empire. For this reason, the city adhered to the provisions of the coinage regulations issued at the Imperial Diet of Augsburg in 1559 when minting its coins. According to these, the obverse should show the origin of the money, which was expressed here by the Zurich shield. For this purpose, the reverse of the coins had to show the imperial eagle and the denomination. The eagle bears a 3 on its breast, this was a 3 kreuzer coin, a so-called groschen.

In the 16th century, material wealth increased, which can be seen in the size of the coins. The groschen on the left (from Latin grosso = thick) is already a stately local coin, the thaler on the right is a symbol that the economy needed a wholesale coin.

Holy Roman Empire, City of Zurich,

The minting of really heavy silver coins began relatively early in Zurich: the first thaler dates back to 1512. At that time, prosperity was flourishing in Zurich, and with it the need for a large silver coin grew. The self-confidence of the rich city dwellers demanded a particularly beautiful coinage.

The minting of really heavy silver coins began relatively early in Zurich: the first thaler dates back to 1512. At that time, prosperity was flourishing in Zurich, and with it the need for a large silver coin grew. The self-confidence of the rich city dwellers demanded a particularly beautiful coinage.

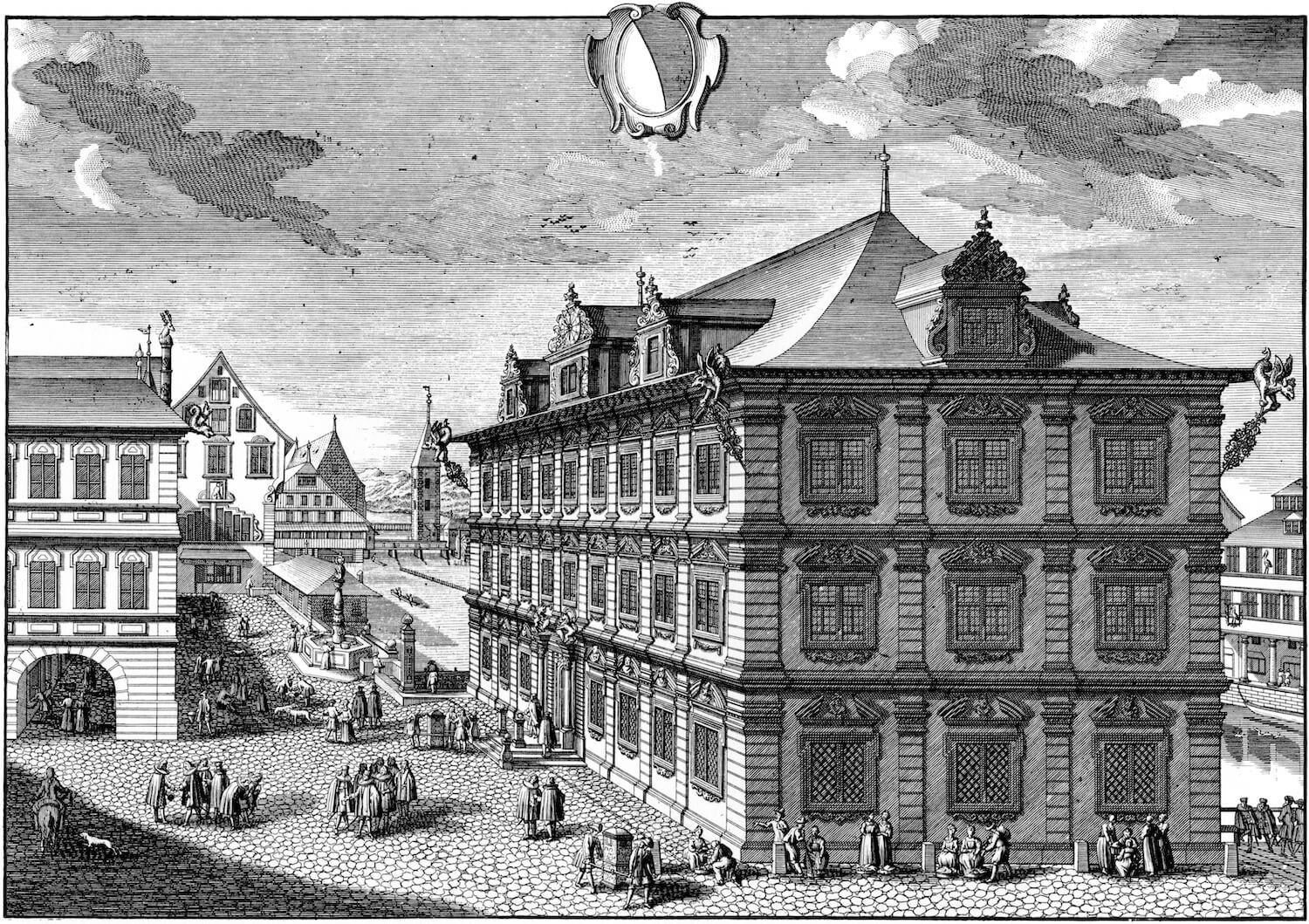

Das Rathaus der Stadtrepublik von Zürich, wie es Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts aussah.

Das Rathaus der Stadtrepublik von Zürich, wie es Ende des 17. Jahrhunderts aussah.

The 17th century: Trade, credit and economic prosperity

While the territory of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation was reduced to rubble during the Thirty Years' War, Zurich escaped relatively unscathed. In the Peace of Westphalia of 1648, the ambassador of the Tagsatzung succeeded in negotiating imperial immediacy for the Swiss Confederation. Zurich then began to proudly call itself the Republic of Zurich.

The depressed production in the German Empire lured the well-funded Zurich merchants to produce for export. The most important export trade in the early modern period was the textile industry. Thus, Zurich developed into an important producer of cloth and canvas, silk and wool as well as cotton fabrics.

The 18th century: Cultural Center

During the long period of peace between 1712 and 1798, material prosperity in wealthy Zurich increased considerably. The city soon became not only a commercial metropolis, but also developed into the center of the bourgeois Enlightenment in the German-speaking world. The latest books of the great philosophers and natural scientists were read and discussed in salons and societies. Because of its geographical proximity to France and the German Empire, Zurich knew and appreciated the books of both French and German philosophers and writers. Zurich became famous throughout the educated world for its cosmopolitanism.

Personalities such as Salomon Gessner, Johann Jakob Scheuchzer, Johann Jakob Bodmer, Johann Kaspar Lavater and Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi were known throughout Europe.

Not only was the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, which still exists today, founded in this century, but also the first state bank, Bank Leu, which was initiated by the Enlightenment philosopher Johann Jakob Leu to offer the citizens of Zurich a secure investment opportunity.

Zurich's prosperity ended in 1798 with the invasion of French troops and the founding of the Helvetic Republic.

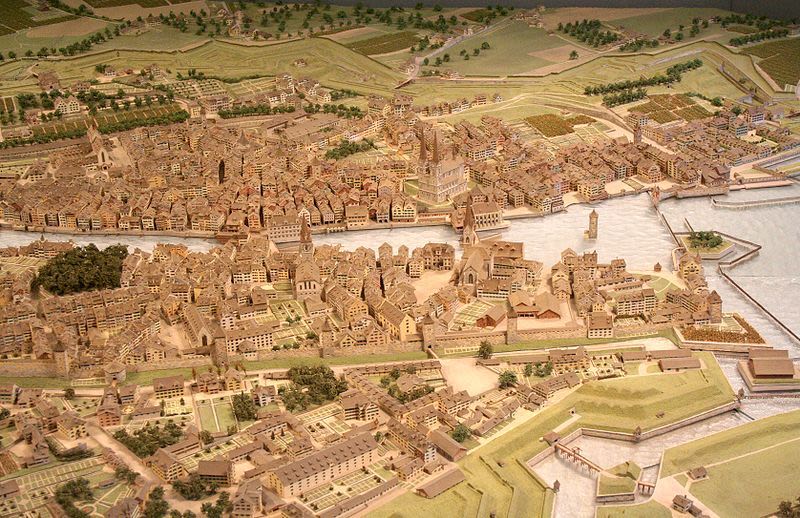

Detail from Zurich city model

Detail from Zurich city model

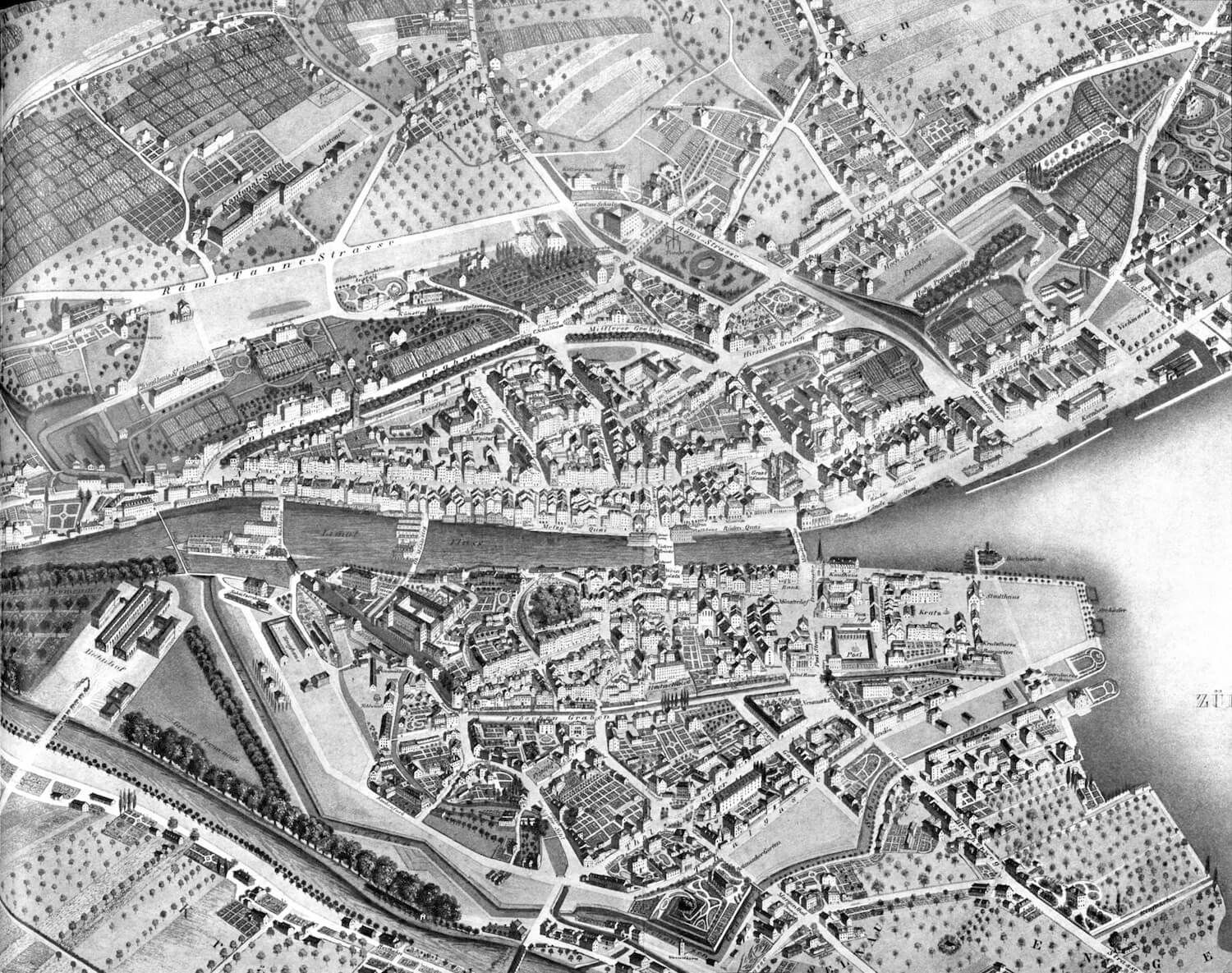

Zurich on the Müller plan of 1793

Zurich on the Müller plan of 1793

Republic of Zurich, double ducat 1716

Many dies for Zurich coins from the first half of the 18th century were made by the well-known die cutter and mint master Hans Jakob Gessner I. Gessner was no longer entrenched in the art of the Baroque, but was already committed to Classicism. This was clearly expressed in his work: the depictions on his coins are no longer lavish and playful, but clearly thought out and of great technical perfection.

Many dies for Zurich coins from the first half of the 18th century were made by the well-known die cutter and mint master Hans Jakob Gessner I. Gessner was no longer entrenched in the art of the Baroque, but was already committed to Classicism. This was clearly expressed in his work: the depictions on his coins are no longer lavish and playful, but clearly thought out and of great technical perfection.

Republic of Zurich, thaler 1715

In the 18th century, the city of Zurich developed a lively minting activity. In addition to gold ducats and their partial and double pieces, silver thalers were also struck. This one shows a powerfully designed lion with the Zurich shield.

In the 18th century, the city of Zurich developed a lively minting activity. In addition to gold ducats and their partial and double pieces, silver thalers were also struck. This one shows a powerfully designed lion with the Zurich shield.

The 19th century:

The message of liberty, equality and fraternity had raised the people's expectations of a fair government that took all interests into account. This could not be satisfied by a council composed mainly of citizens of Zurich, as long as it represented the interests of the city dwellers exclusively. Since 1829, freedom of the press had prevailed for the Zurich media, and they, fueled by the Paris July Revolution of 1830, demanded political, social and economic equality between city and country, a postulate that was realized with the constitution of 1831. It made Zurich a model liberal state that was to offer asylum to revolutionary thinkers from all over the world.

As a visible sign of the equality of city and country, it was decided in January 1833 to grind down the city fortifications, which for centuries had served as a border between the privileged city and the underprivileged countryside. Freedom of trade and commerce was introduced and the school system reformed. This created the basis for rapid industrialization, which demanded a new kind of entrepreneur, but also a new kind of employee.

Zurich after the demolition of the redoubts.

Zurich after the demolition of the redoubts.

The Sonderbundkrieg, the last military conflict on Swiss soil to this day, ended the coexistence of independent states. With the Federal Constitution of 1848, Switzerland united to form a federal state. At the same time, the federal state created a unified economic area that was held together by a customs and coinage union. It offered entrepreneurs optimal conditions for implementing their ideas of progress.

Today, Alfred Escher (1819-1882), celebrated by his contemporaries as the "Czar of Zurich", is considered the prototype of the Zurich entrepreneur. He founded several private railroads, of which the Gotthard Railway has probably become the most famous. It is not without reason that his monument stands today in front of Zurich's main train station. To raise the necessary capital for railroad construction, Escher created the Schweizerische Kreditanstalt, thus establishing Zurich's financial center. He also initiated the Federal Polytechnic (now ETH), which did not offer a fine arts education like the university, but focused on technology and the natural sciences, a completely new concept in the 19th century.

Alfred Escher - a man with vision, who made Zurich a business metropolis on the basis of a modern educational institution and a credit institute.

Alfred Escher - a man with vision, who made Zurich a business metropolis on the basis of a modern educational institution and a credit institute.

The flip side of the rapidly advancing industrialization was the impoverishment of a large part of Zurich's population. In some urban areas, veritable slums sprang up, housing working-class families whose incomes were far below the subsistence level. The industrial areas along the Limmat depended on the exploitation of the cheapest labor, so that Zurich society in the 19th century was deeply socially divided.

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH), founded in 1855.

Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETH), founded in 1855.

Schweizerische Kreditanstalt, today CS. Founded in 1856 by Alfred Escher to raise capital for various projects, most notably the construction of the Gotthard Tunnel.

Schweizerische Kreditanstalt, today CS. Founded in 1856 by Alfred Escher to raise capital for various projects, most notably the construction of the Gotthard Tunnel.

The 20th century: Red Zurich and Bourgeois Society

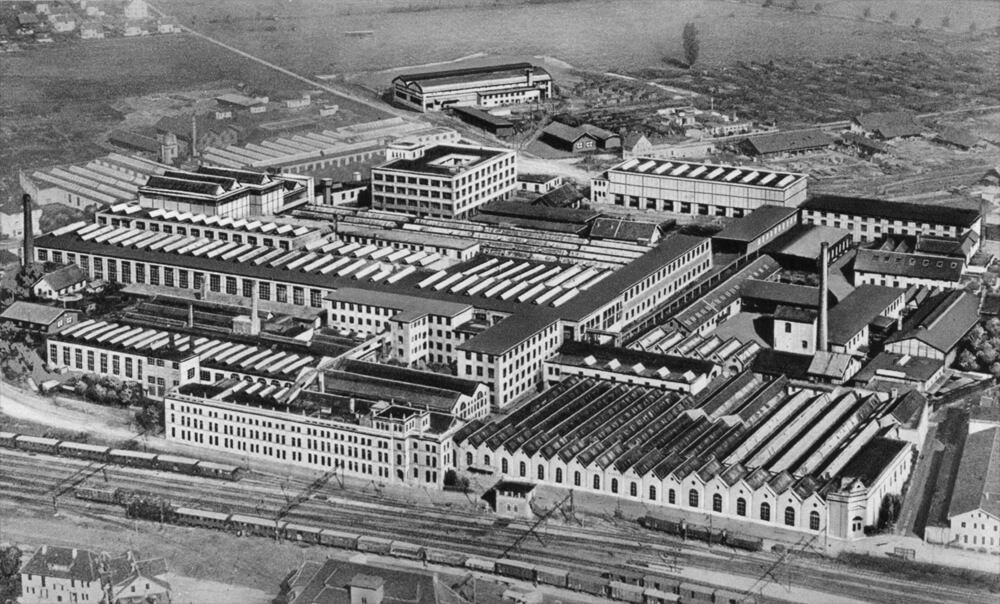

The arms factory in Oerlikon. For a long time the most important employer in Zurich.

The arms factory in Oerlikon. For a long time the most important employer in Zurich.

Like all European cities, Zurich grew enormously from the end of the 19th century, a development that accelerated in the 20th century. The many workers' settlements that were incorporated into the city changed the political climate. The bourgeois city became a workers' city, where revolutionaries like Lenin found refuge. During the First World War, Zurich was considered the center of the radical leftist movement in Switzerland, but at the same time it developed avant-garde traits in art. Dadaism emerged in the Cabaret Voltaire, not far from Lenin's Zurich apartment.

In 1928, the Social Democratic Party obtained an absolute majority in Zurich for the first time and maintained its dominance until 1949. It was this climate, together with Swiss neutrality during World War II, that made Zurich an exile for Europe's intellectual elite expelled from Germany. The Zurich Schauspielhaus became the most important German-language stage.

The contrast between small-scale development and the cosmopolitan economy has always pervaded the city's politics.

After the end of the Second World War, Zurich developed into an international trading and banking center.

But again, we have arrived at a historical turning point: Prosperity has to be reinvented, also in Zurich.