Historical Foundations of

Chinese Cultural DNA

THE "CHINESE IDENTITY"

In contrast to "Western" individualism, characterized by rationality to overcome any structure that could inhibit progress, and reason as the universal judgement authority, "Chinese" collectivism is defined by the "right way":

from Taoism, the "mind" from Buddhism, the "body" (actions toward others) from Confucianism, and the foundations of diplomacy, persuasion, deception, cunning, and strategies of outstanding figures such as Guǐ Gǔ-Zi (410-320 BC, famous strategy and master of the art of war).

The decisive shaping and standardization of the characteristics of "Chineseness" took place in the Spring and Autumn period (770-476 BC), as well as the period of the Contested Empires (475-221 BC) of ancient China.

The basic term for 'Chinese' in the Chinese language is 'Huá-Rén', which places the historical-cultural identity as descendants of 'Huá-Xià' (ancient self-description of the Middle Kingdom) in the time of Confucius (551-479 BC). The "Book of Deeds" from the early Eastern Zhōu period (771-256 BC) reads, 'Our illustrious and great country [Huá-Xià] and the tribes of the south and north alike follow and agree with me.'

Based on the foundation of "Chineseness," the Chinese Communist Party institutionalized the term "Guó-Qíng" as "China's special nature" or "China's characteristics" at the founding of the PRC in 1949 (especially in the wake of the "Open Door Policy" initiated by Dèng Xiǎopíng in 1978) and defined this as "background noise" to legitimize its own claim to power, obtaining the "Mandate of Heaven."

Water is the only chemical compound on earth that occurs in nature as a liquid, a solid and a gas. Lao Tzu quote: The highest good is like water. It benefits everyone, but it does not quarrel with anyone.

THE PRE-QIN ERA - ORIGINS OF CHINESE HISTORICAL AND CULTURAL DNA

Traditional Chinese history, in a narrow sense, includes the Xià (2070-1600 BCE), Shāng (1600-1046 BCE), Western Zhōu (1046-771 BCE), Spring and Autumn periods, and the Warring States period.

This period represents the origin and founding time of ancient Chinese civilization.

The conquest of the Shāng by the Zhōu in 1046 B.C. marked a milestone and became an illustration of the irrepressible will of Heaven, which transferred its "mandate" (the order to rule) from one state to another blessed with virtuous rulers.

During the Spring and Autumn period, the Zhōu royal house increasingly deteriorated and lost its status as the "ruler under heaven". In the 700s BC, the feudal system known as "Fēng-Jiàn" began to collapse. The power struggles that the many small states fought with each other brought 250 years of war turmoil and chaos to the country, a period referred to as the Warring States Period.

The most significant development during this period was the great breakthrough in the intellectual field.

The 'Spring and Autumn Period' breakthroughs initiated primarily by Lǎo-Zi and Confucius eventually led to the formation of a permanent, collective identity - "Chineseness."

Lǎo-Zi

With 'Dào' as the core of his teaching, Lǎo-Zi pursued in his diplomatic thought an order defined by 'Wú-Wéi' (not engaging in human intervention, but letting everything develop naturally) and naturalness. At the beginning of Lǎo-Zi's classic work of Taoism 'Dàodé Jīng', the concept of 'Dào' is explained: 'The path that can be walked is not the permanent and enduring path; the name that can be named is not the permanent and enduring name'.

The 'Dào' of Taoism thus describes the way, principle, truth, morality, reason, or method of all living beings. The 'Dào' is the ideal form of existence in the universe, and the relations between states should adhere to the principle of the 'Dào'.

Confucius

As a traveling advisor, Confucius offered his services to the rulers of various states of the then Zhōu Empire. Although he was largely unsuccessful in implementing his ideas, the philosophical foundations he laid became the core texts of the Chinese dynasties. Confucius did not envision society as an equal system full of different individuals, but rather he saw it as a series of relationships between people with defined roles.

Confucius established a pattern of thought and cultural heritage that more people have followed for more generations than any other human being on earth. No matter what religion, no matter what form of government, Confucian elements can be found in some way in the thinking and actions of Chinese and most other East Asian civilizations. Despite the changes we see in modern China today, its teachings continue to indirectly influence the way Chinese think and feel about the world.

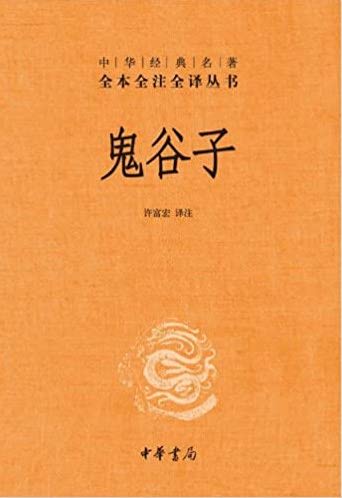

Guǐ Gǔ-Zi

The "Master from Demon Valley" lived in the midst of the turmoil of the Contested Empires, in which vast armies of the various empires were led by commanders who had abandoned the supposed chivalric etiquette of warfare in earlier times and ruthlessly waged campaigns to destroy the enemy. The period between 770-221 BC was one of the most divided in Chinese history, with some 395 battles fought during the Spring and Autumn period and 230 battles fought during the Warring States period.

During this time of turmoil and chaos, Guǐ Gǔ-Zi pioneered the 'School of Vertical and Horizontal Alliances', which states that in international competition, strategic planning is a key factor in a nation's success or failure. Guǐ Gǔ-Zi is considered the father of strategies, negotiation skills, cunning, deception, and diplomacy, which are still a core element of 'Chineseness' today.

Basics of Chinese Historical and Cultural DNA

What are essential features of Chinese historical and cultural DNA that were created by the great philosophers, thinkers, and masters of strategies during the crucial periods from the Western Zhōu to the imperial unification by the Qín Dynasty, thereby shaping the uniqueness of "Chineseness" and refining it over millennia?

Firmness and strength of character (Gāng-Jiàn)

The idea of 'ceaseless pursuit of self-improvement' has inspired many Chinese intellectuals throughout history. Confucius emphasized 'firmness and strength', while Lǎo-Zi valued 'gentleness and softness', both of which continue to exert far-reaching influences today.

"Firmness and strength" and "self-improvement" of Confucianism, as well as the doctrine of "tranquility and non-action" of Taoism, have played a fundamental role in consolidating Chinese identity throughout history.

The Golden Mean (Zhōng-Yōng)

Confucius put forward the concept of the "Doctrine of the Middle," which continues to exert a strong influence in Chinese culture today.

The "golden mean" is the moral standard of Confucianism - to treat people and things neutrally and peacefully, to adapt to the times (to use ways and methods according to the current situation), to adapt one's actions to the nature of people and things, to conform to the circumstances at hand - that is, to act in accordance with human nature, from which the theoretical roots of Confucianism originate.

Holistic culture

In the holistic traditional culture of China, "group and self", "public and private", the relationship between "individual and state", and between "individual and world" are holistically interconnected. Emphasis on the interests of the whole, harmony and unity of the collective, emphasis on moral obligation of the individual and loyalty to the collective, have always been values emphasized by Chinese traditional culture.

"Chineseness" in the traditional context means "common Chinese cultural identity": all Chinese bring their thoughts, actions, and lives in society into conformity with "Tiān-Mìng," the 'principles sanctioned by heaven.' Individuals and society are expected to behave in a 'civilized' manner in language, social interactions and daily life.

The expectation of modest courtesy on the part of individuals and society as a whole represents an indispensable necessity for people to live together peacefully in the face of China's immense population. This basic assumption of "Chineseness" through Confucianism is deeply rooted in Chinese culture.

Stand out by customizing

In the course of Chinese history, the DNA of "Chineseness" consisting of the main elements Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, enriched with the knowledge of strategies, diplomacy, deception and persuasion, has been tested, refined, adapted and strengthened over thousands of years.

In doing so, it usually proved best to sometimes apply 'Confucianism outwardly and Buddhist teachings inwardly (the following of laws and order of the cosmos')', or sometimes 'firmness and strength outwardly and gentleness and softness inwardly': this enables an enormously rapid adaptation to changed circumstances, the power of the sovereign can be limited by "Wú-Wéi" to the most necessary. This is the only way that China's reform and opening-up policy since 1978 could have been tackled at all and finally successfully implemented.

Regarding Confucianism and Daoism, the famous Chinese literary scholar and scholar Nán Huáijǐn (1918-2012) once drew the following analogy:

'Confucianism is like a granary: it must not be fought [beaten, attacked]. Otherwise, if Confucianism is defeated [overthrown], people will have no food to eat - no spiritual food;

Buddhism is like a department store in a big city: there are all kinds of daily necessities, and you can go shopping whenever you want; if you have money, you can buy a few things, if you don't have money, you can just take a tour, no one is prevented [from going there or entering], but everything inside is necessary for life;

Taoism is like a pharmacy: if you don't get sick, you don't have to worry about it for the rest of your life, but if you do get sick, you automatically have to go there.'