Descartes –

Founder of modern philosophy

Descartes played an important role in the scientific revolution of the 17th century.

Opera Philosophica, Amsterdam 1685

What can we really know?

The emphasis is on: really. Today we call this branch of philosophy epistemology. Its founder was one of the titans of intellectual history: René Descartes.

Along the way, he produced fundamental works in the fields of mathematics and natural sciences. Two of his central works appeared in the scientific language Latin in 1685 in Amsterdam under the title Opera Philosophica, i.e.: Philosophical Works.

Before we take a look at it, let us ask ourselves why this book, which, besides everything else, wanted to prove and not disprove the existence of God, ended up on the notorious index of the Roman Catholic Church ...

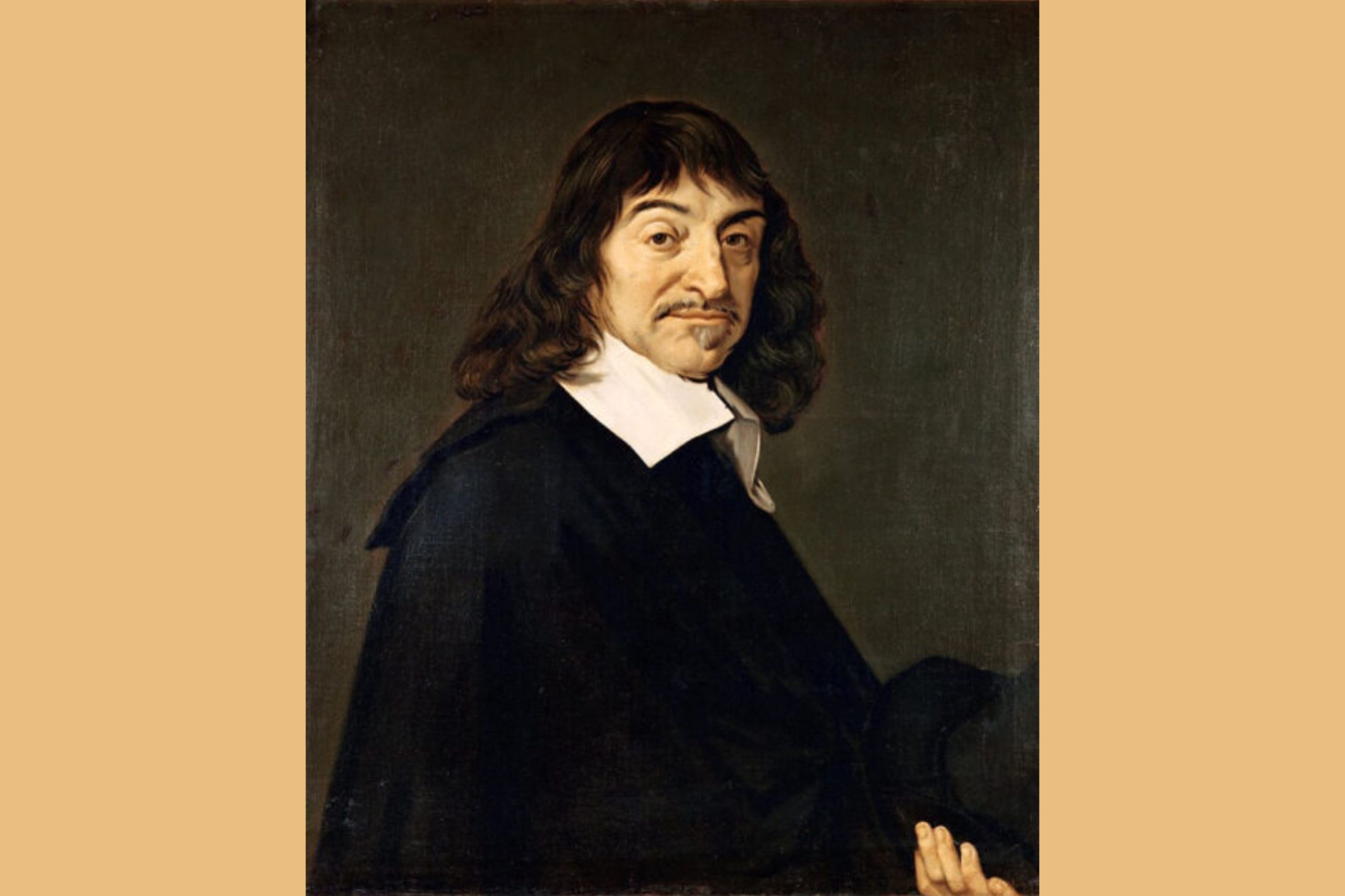

Descartes – Visionary and enlightener

Let's start in Ulm, in a hut during the Thirty Years' War, in the middle of a cold night. Sitting by the stove, the young René Descartes supposedly had a kind of vision. He was pondering what in the world we can actually recognize as it is. Our senses are always playing tricks on us and are unreliable.

Perhaps our thinking? But can't that also be manipulated? But not our doubts! If we doubt, then there can be no doubt that we just doubt. Descartes was to carry this fundamental insight around with him for decades and to look at and analyze it again and again from all sides like a cherished piece of jewelry. It crystallizes in the famous dictum:

I think, therefore I am.

Descartes was born in Bretagne in 1596 as the son of a lower nobleman and enjoyed an excellent education, studied law, and traveled through Europe as a soldier in the service of various lords. Along the way, he came not only to Ulm, but also to the study rooms of astronomers Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler. The young man was convinced of two things. First: There must be a universal method for the investigation of truth. Second, he, René Descartes, was destined to discover that method.

Descartes sought exchanges with scholars and began to publish. Then came a shot across the bow:

The trial of Galileo made it clear to him what danger he himself was in. Descartes wanted to prove God in his Treatise on the World. However, in a scientific work.

And how thin-skinned the church reacted had been seen in its reaction to the writings of the devout Catholic Galileo. It was not enough to prove God, the rest of the world view had to be right. And for Descartes it did not, as we shall see. So he left this draft in the drawer to be on the safe side.

For unlike Galileo, Descartes did not write in Latin. He thought, not without reason, that his thoughts were too important to be made accessible only to his colleagues in their ivory towers. Therefore he wrote in the language of the (French) people, he saw himself in the best sense as an enlightener.

Descartes' Treatise appeared anonymously in 1637. The work was aimed at a broad readership in French. It was not until 1656 that the work was translated into Latin.

Enemies everywhere

But this enlightenment did not please everyone. After the buried treatise on the proof of God, Descartes published a work that also contains our edition: His "Treatise on the Method of Using His Reason Well and Seeking Truth in the Sciences. The work was initially published anonymously. Nevertheless, all of Europe knew who was behind the work. For good reason, Descartes had retreated to the relatively liberal Netherlands.

He certainly believed in God, but above all he was convinced that God had created a world that functioned independently of him according to fixed laws.

And the task of the scholars was to recognize and describe these rules. So within nature, there was no longer a need for an intervening God. Today we call this new school of thought rationalism. This was strong stuff. Descartes found himself attacked from many sides and feared reprisals. He wandered restlessly across Europe. He corresponded with the intellectual giants of his time, but always through a good friend in Paris, who was the only one who knew Descartes' changing addresses.

He who thinks is. But what is he?

Descartes had made a fundamental turnaround in thinking. Until now, philosophers had sought to describe the world as it is. Descartes took a step back and asked: what can we know at all? He realized that we work with ideas, formed in our heads, so we cannot gain objective knowledge at all. The birth of epistemology.

Curiously, the "Treatise" of 1637 presents itself as a kind of autobiography. The author demonstrates the procedure by his own life story and his growing understanding of epistemology. He takes the reader by the hand and explains how to argue cleanly and clearly, step by step. There is no mistaking the mathematician's signature.

Our edition presents a Latin text that appeared in Amsterdam in 1656, by now under Descartes' name. Playing hide and seek was no longer necessary.

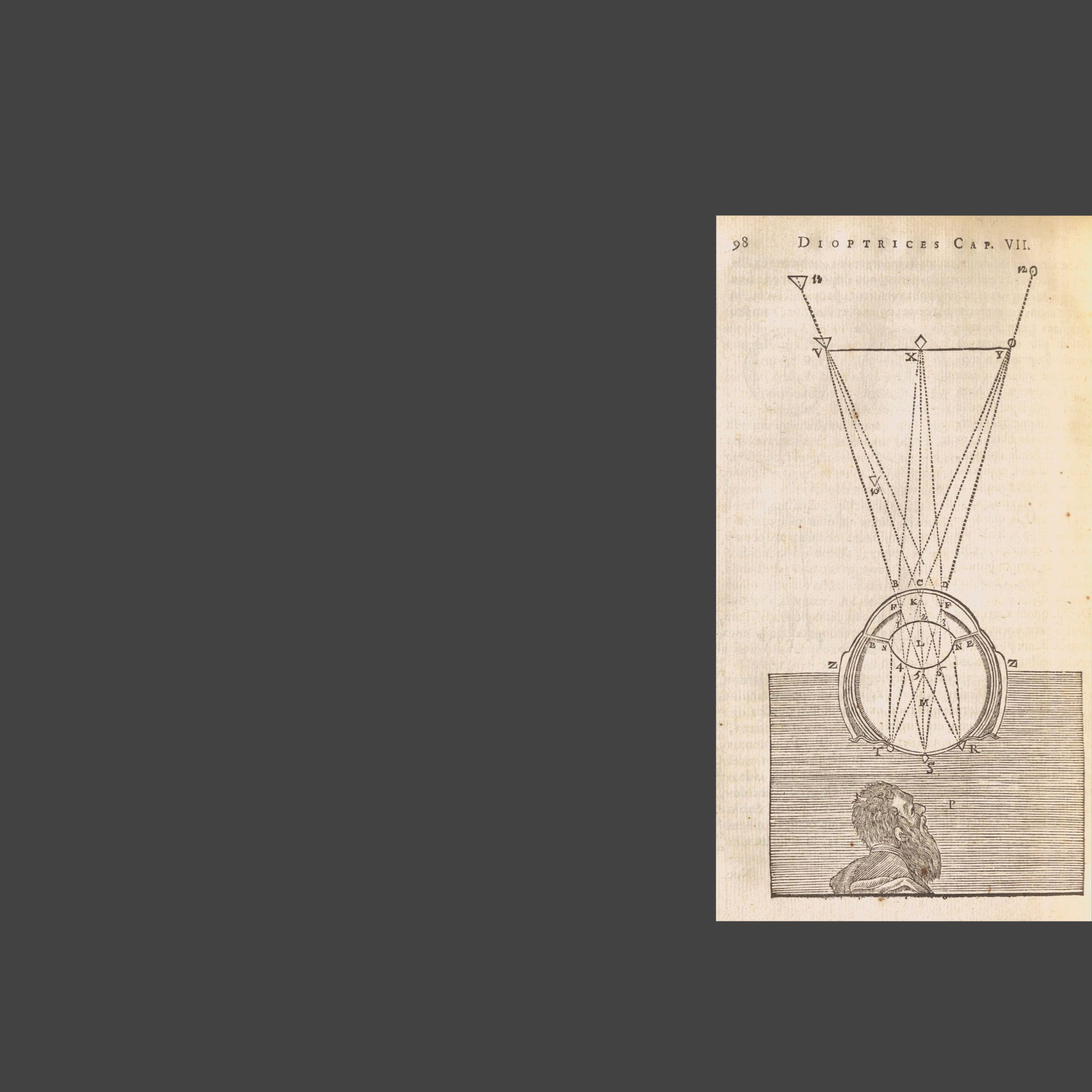

Very practice-oriented, the author demonstrates his method by means of three topics he examines: Refraction of light, celestial phenomena and analytic geometry. We see: The man was not only a philosopher, but also a physicist, astronomer and above all a mathematician.

But Descartes also asks about the concrete application to ethical questions. This was a much bigger problem, because Descartes' complex, we could say infinitely picky, analyses would keep modern high-performance computers like Deep Blue busy for years. That's no way to solve everyday problems. So Descartes advocates provisional ethics, practiced temporarily until one has definitive answers. A pinch of pragmatism, in order to live with the high claim of the perfectionist with his head held high.

It is in principle

A few years after his "Treatise," in 1644, Descartes had another book printed, this time in Latin and thus explicitly addressed to his colleagues: the "Principles of Philosophy" ("Principia Philosophiae"). They are dedicated to his pen pal and eager student Elisabeth of the Palatinate. In order to open his thoughts to more readers, Descartes also had this book translated into French three years later. Our edition contains a revised later version of the first Latin text.

In this work, Descartes tries the big shot. It is indeed the first mechanistic interpretation of the world and its laws. A milestone in the history of philosophy. Here Descartes mentions in passing what we know today as the law of inertia or Newton's first law: Bodies remain at rest as long as no external force acts on them. Newton later borrowed this from Descartes.

The edition of 1685, published a generation after Descartes' death, is composed of these two works, the "Treatises" and the "Principles", both in revised editions and Latin, still in the author's care. As was customary at the time, the main writings were printed again and again and sometimes distributed individually, sometimes bound together in different compilations.

At that time, the influential Jesuits had long since ensured that everything Descartes had ever published ended up on the index. Whether Descartes believed in God or not did not matter to them. A world that could be explained without the direct action of God was inconceivable to them. But this naive attempt to sweep a new worldview under the rug did not, of course, prevent these books from being printed and read anyway. For centuries, Descartes was among the most influential figures in the history of philosophy. Anyone who looks into this book can understand why.

by Björn Schöpe