Money

from

Aristoteles

to Bitcoin

Book_Collection

Are Coins Money?

Since when has money existed? Since coins were minted, or since modern times, or perhaps money has always been in existence? Coins are money for us, and the ancient world also knew coins - but does that mean that coins have always been money? Two well-known representatives of their time provide the answer: Aristotle and Petrarca.

Aristotle, philosopher, Athens, mid 4th century. He is considered the most famous first theorist of money. Important for us are his books on ethics (Nicomaean) and Politika on the state. The book of ethics is about justice, about the middle of the right measure. In exchange within a community, there needs to be balance, and a just balance must take into account the inequality of the participants. When this kind of proportion is taken into account in compensation, retribution and reciprocation are realized, and this is the basis of the polis, the Greek community. There are, as Aristotle presents, necessarily four quantities to consider when it comes to just compensation: not only the two goods exchanged, but also the two exchangers themselves. For to society, individuals are unequal, have different importance. What is exchanged according to equality and proportion must somehow be comparable, and coins are there to provide that comparability, Aristotle writes. He defines the one thing that makes all things comparable, not as value or something calculable in numbers, but as need. Aristotle does not think of specifying how the value of something is calculated, but describes under what circumstances a price may be considered reasonable and just. Chremata is often mistakenly translated as money, but it was used to describe all useful things.

In the Politica, Aristotle devotes himself in detail to the subject of possession and acquisition. The true wealth is called plutos. There it says that the acquisition of coins in order to acquire coins again has no barrier, quite contrary to true and natural wealth, and is therefore unnatural. Because this contradicts the idea that the exchanged things should be adequate to each other. All this contradicts our concept of money and value, of buying and selling. Aristotle's concept and our concept of money are so different that the conclusion is obvious: the ancient world did not know money as we use the term today.

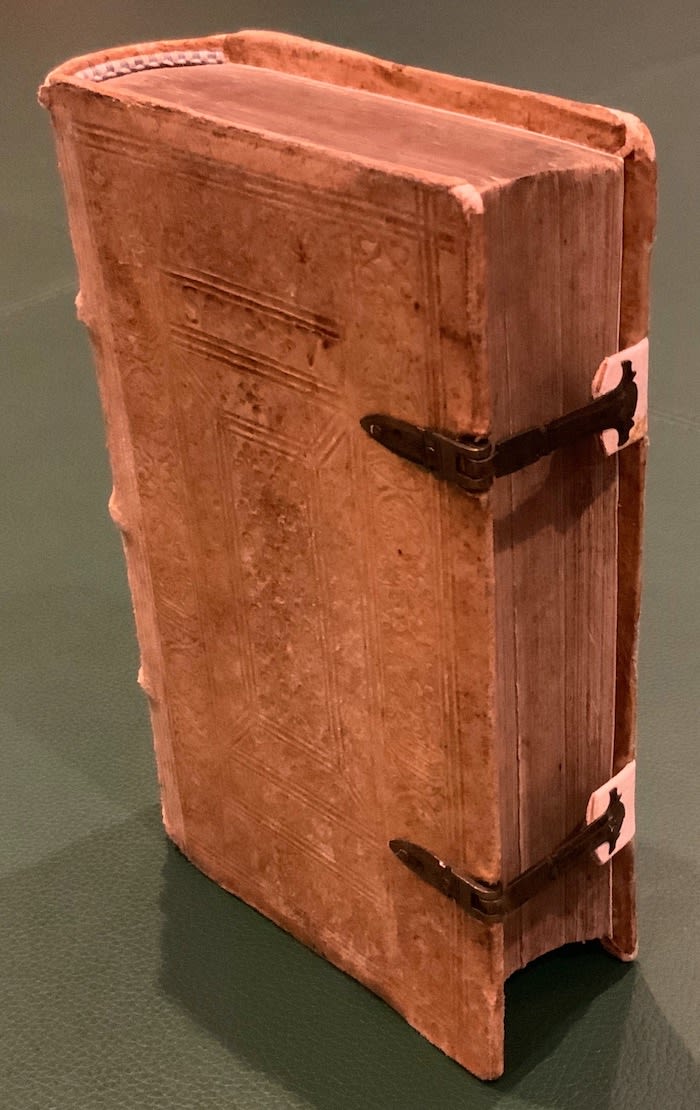

book on ethics (Nicomaean), Strassburg 1549

book on ethics (Nicomaean), Strassburg 1549

Peloponnes, polis of Elis, Stater, 363 BC, shows father of the gods zeus.

Peloponnes, polis of Elis, Stater, 363 BC, shows father of the gods zeus.

Syrakus, Sicily, Dekadrachme, BC.

Syrakus, Sicily, Dekadrachme, BC.

Head of Arethusa on reverse of coin, by Euainetos.

Head of Arethusa on reverse of coin, by Euainetos.

What about the Middle Ages? There were coins there. Petrarca should know whether there was money in our sense in his time.

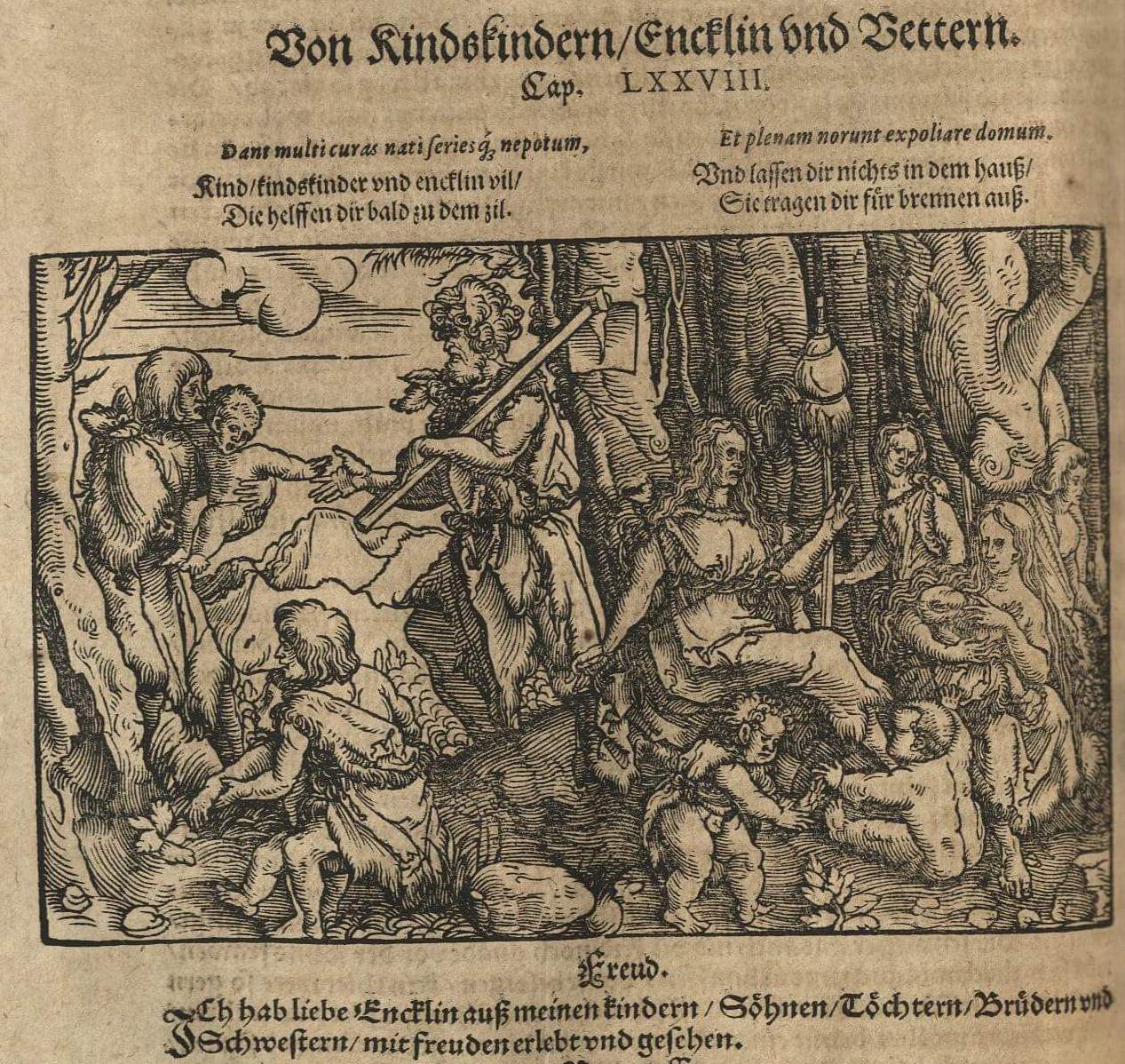

Luck and misfortune are fate. What is important is our attitude. The Italian Renaissance poet Francesco Petrarch (1304-1374) was convinced of this. This "comfort mirror" was written in 1370. By 1756, the bestseller had gone through 28 editions in its original Latin edition alone and was translated into more than 50 languages. The book was originally written in Latin, but for the 200th anniversary it was translated into German; one of the best Renaissance artists was engaged for the woodcut. Thus, the book presents 250 everyday situations from the life of medieval man, with brief description and Petrarch's advice. You have to leaf through the book slowly and curiously pay attention to what problems these people had: is it health, reputation, activity, partnership, maybe coins, loans and worries with money?

Health is mentioned often, also the fatherland. Coins, on the other hand, are mentioned only five times, and when they are, then as a dowry or in the case of theft. Loans, the need for profit, taxes or even financing do not occur. The most frequent image: "Blessed is he who is well-born"; the hierarchy in the Middle Ages was predetermined. There is no trace of buying and selling, of money in our sense.

Francesco Petrarca, Comfort mirror in happiness and misfortune, Frankfurt 1572

The big rethink

In the so-called "long 16th century", which extended far into the 17th century, a change in the world view took place. By what did people recognize that money, our modern money, had come into being? We look at the 16th century folk book Fortunatus, the Jesuit school of Salamanca, the statements of the economist Misselden in 1622 and the description of rhythm as a beat rhythm by Descartes in 1618.

From win-loose to win-win:

Aldo Haesler, a professor of sociology at the University of Caen in France, has spent years studying the transition from the Middle Ages to modern times. What exactly had changed then? In his opinion, it was primarily the change from the win-loose world of thought, in which one person's gain must be another's loss, to the win-win world, in which everyone benefits. From the closed order, which was hierarchically structured, with a finite space, to the open world order. The previous conception shattered because of the impossibility to maintain certain dogmas against calculations and observations. A change of the world view occurred. Aldo Haesler calls it the transition from the zero-sum game to the positive-sum game.

What is new is that man does the same with success - he owes it to no one, only to himself. This formula of modern emancipation was unthinkable in traditional societies; unthinkable because all relationships among people were mutual debt relationships. At the beginning of the 17th century, the merchant was still spoken of as a parasite; by the middle of the century, he had become an agent of Providence. Money is no longer just a tool, it has become a medium, a language with numbers that is universally available.

The Jesuits of Salamanca:

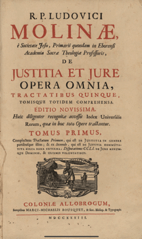

Luis de Molina, De Iustitia at Iure, 1602

Luis de Molina, De Iustitia at Iure, 1602

The School of Salamanca gained importance through the development of an "international natural law. Against the background of the conquest in South and Central America by the Spanish and Portuguese, humanism and the Reformation, the traditional conceptions of the Roman Catholic Church came under increasing pressure in the 16th century. The School of Salamanca tackled the resulting problems. Its goal was to harmonize the teachings of Thomas Aquinas with the new economic-political order of the time.

The theories of the Salamanca School heralded the end of the medieval concept of law. In a way unusual for the Europe of that time, they demanded more freedom. The natural rights of man (right to life, right to private property, freedom of expression, human dignity) became the center of interest of the School of Salamanca. According to Diego de Covarrubias y Leiva (1512-1577), people not only have the right to private property, but also the right to benefit exclusively from the advantages of property.

Winckler, Nicolaus, Bedencken Von Künfftiger verenderung Weltlicher Policey vnd Ende der Welt, Augsburg 1582

Dr. Winkler, Faust von 1582

Dr. Winkler, Faust von 1582

"Faust," who questions existing knowledge and strives for wisdom, is not an invention of Goethe, but was a popular book of the 16th century. Nicolaus Winkler, a physician in Augsburg, published it in 1582. The end of the story: Faust dies. Popular sentiment at the time saw questioning the existing order as an outrage, so Faust had to die - in stark contrast to the version 200 years later. Goethe had recognized "the great rethinking" and capitalism and introduced the wager between Faust and Mephisto with the prohibition of lingering. Goethe is a highly respected author today, but most readers do not understand this passage of the capital function; we cling to old ideas, just as people did in the 16th century. Even then, Goethe seems to have anticipated this and only released his work for publication posthumously.

Fortunatus, London 1740

Fortunatus, London 1740

At the beginning of the 16th century, Fortunatus began to be distributed as one of those "folk books”, as the Romantics later christened them, since no author was given. Among these "folk books" are also celebrities such as the Eulenspiegel and the book of Doctor Faustus. Fortunatus is present all over Europe, and for more than 200 years the story of the never-ending purse finds many readers there. First edition was in 1509.

Fortunatus received a sack with never-ending coins in it. This reminds me of lottery millionaires who suddenly have great wealth without a track record. What does Fortunatus do now with his new wealth? Fortunatus doesn't rest on his sack, but sets out to cross the world as a merchant and in this way to become rich. For one could only imagine the merchant's capital. What his coins bring him at home is indeed significant, it makes him a noble lord over land and people, but it remains limited. Inside the commonwealth, Fortunatus gets only limited things to buy for his coins.

Misselden, Free Trade, 1622

Misselden, Free Trade, 1622

Misselden is the author of "Free Trade, Or the means to make trade flourish," 1622. As a mercantilist, he made an important contribution to the idea of the balance of trade. "Money has now become the price of all things," Misselden wrote in 1622. For the first time this statement is verifiable, money is now ascertainable. His sentence "As to its nature and as to its succession in time, money comes only after commodities, but as it is in use today, it became the main thing," corresponds to the modern conception of money.

Descartes, Musicae Compendium, 1618

Descartes, Musicae Compendium, 1618

Descartes writes a book about music in 1618, describes the notes, the rhythm. For the first time he uses the term "beat rhythm" to describe rhythm. This is amazing. Something must have changed in the minds of the people of that time, because they felt a different rhythm only 50 years before.

Descartes writes: The time measure of the tones must consist of equal parts, because these are most easily grasped by the sense of hearing ... This division is marked by a beat or the so-called precipitation, which is done to support our imagination ... like the war drum, where nothing but the measure of time is heard ...

Where does this change come from? The answer had to wait for centuries until Eske Bockelmann picked up the thread and meticulously proves exactly where this change, this unconscious reflex in the perception of rhythm comes from. He wrote the work "Im Takt des Geldes” (To the Beat of Money).

Stockalper Schloss in Brig, Wallis.

Stockalper Schloss in Brig, Wallis.

Stockalper's anagram – sospes lucra carpat

Stockalper comes from a patrician family from the Valais, which used to own a Stockalpe on the Simplon Pass. Hence the name. At the age of 20, he completed his education at the Jesuit Academy in Freiburg im Breisgau, mastered six languages and wanted to enter politics in Brig. Valais was in the middle of the field of forces of the great powers: in the west the Habsburgs with Spain, the Duchy of Milan and the Spanish Netherlands; France was trying to free itself from this grip. The passes in the east were caught up in the turmoil of war and failed.

Stockalper then recognized the strategic importance of the Simplon Pass. He extended the Simplon Pass, obtained the monopoly for the transport of goods, later also the salt monopoly and the mercenary monopoly. As an entrepreneur, he takes over an iron smelting plant in Valais from bankruptcy. He expands his activities into a conglomerate, in which many synergies open up. The close interlocking of politics and business was one pillar of his success, the other was the use of the debt trap: he often granted generous loans to farmers, letting the interest accrue until the point where he could snatch the land from the farmers. In this way he became the largest real estate owner in Valais. Simplon transit, salt and mercenaries were his three fields of activity, with which he amassed enormous wealth. All this can be seen in detail in his account books, which he meticulously kept himself.

Scruples? He had none. After all, the latest realization of the win-win situation was his life motto: "Sospes lucra carpat" - God's favorite shall skim the profits. Motto and anagram of his name. Threats, bribery, patronage, shear money, vote buying were part of the arsenal of his activity. Until his fellow citizens no longer cooperated. A coup, deprivation of power, Stockalper fled to Domodossola.

Stockalper is an example of the new money order, economically, socially and spiritually. Even today, the oversized palace in Brig bears witness to his ambitions. On the positive side, he recognized that Switzerland, as a small state in the center of the continent surrounded by great powers, had to take an opportunistic approach to its neighbors. On the negative side, he embodies the new way of dealing with money, with the urge for more and more profit, control and continuous capital accumulation.

Picture by National Geographic: Mughal emperor Shah Alam II grants Robert Clive, leader of the East India Company’s army, the ability to collect taxes in Bengal.

Picture by National Geographic: Mughal emperor Shah Alam II grants Robert Clive, leader of the East India Company’s army, the ability to collect taxes in Bengal.

Conquering new markets

The capital-oriented market economy has been carried out from Europe into the wider world since the 17th century. As an example, we have the East India Company, which developed from a trading company into the most powerful corporation in the world. We can see from it that the new money must inevitably lead to the conquest of new markets; moral concerns were pushed aside by reinterpreting the "invisible hand" of Adam Smith and the neoliberalism of Walter Lippmann.

East India Company

Around 1600, the East India Company was founded. And not as a limited partnership, as was customary at the time, but as a stock corporation. With this, it was possible to raise far more capital, because the circle of financiers was unlimited. Initially a trading company, but with the right to its own army, the company developed into a powerful enterprise in the 18th century. By 1800, the company had an army of 260,000 soldiers in India, twice as many as the English army. As a company, however, it was responsible only to its shareholders. It is popularly said that the English had conquered India; but it was the East India Company which had taken Bengal with its private army and collected the taxes there for itself. And like Stockalper before it, or the great multinationals after it, the close connection between business and politics was crucial to its success; the East India Company maintained close ties with the British Parliament by transferring shares in the company to politicians. By the end of the 18th century, the company was finally "too big to fail" and had to be rescued by the British government because it was operating with a lot of leverage and little equity.

What was new about the East India Company?

- First, the concept of the joint-stock company to raise capital, as opposed to the family companies with limited shareholders that were common at the time.

- Secondly, the extent of scruppelless profit maximization.

What does the example show?

- First, the example shows how capitalism was carried from Europe to the whole world.

- Second, the example shows how market economies without state governance lead to extreme situations.

- And third, this example shows the effect of the fatal link between business and politics, which leads to monopoly positions.

The End of History?

The development so far shows that money has evolved from a tool to an economic and social system. It pushes for the conquest of new markets, which drives innovation, but also for reckless expansion and exploitation of resources and people. Our money is in crisis; not only because global expansion has reached its limits, but because a large part of the population no longer wants to participate. Has the end of this monetary system been reached?

Karl Marx' Thesis

Karl Marx, Das Kapital, first edition was in 1867 in Hamburg with a starting print run of 1000 copies. Book II followed in 1885, Book III followed in 1894. Our edition: Complete Complete Edition in 3 volumes in slipcase, 2016.

In 1867, Karl Marx published his work "Das Kapital" after spending several years in London studying the nature of money. The impact of his work was enormous. However, he would never have approved of the idea of communism as it developed over the next 100 years. Marx's thesis was that the development of the capital-oriented market economy, capitalism was in a terminal phase because of the increasing division of society. A few capitalists would have most of the capital, and the population would form the proletariat. Therefore his advice: "Proletarians of all the world, unite". Why did his theory fail? Although he studied the nature of money for some years, he never dealt with the genesis of modern money. He presupposed money. Thus, he defined "value" as "labor value," that value which is performed by labor. It is the merit of Eske Bockelmann to get to the bottom of this theory of value and to set it right.

Fukuyama: The End of History, 1992

Fukuyama, an American philosopher and historian, in his 1992 work "The End of History and the Last Man" put forward the thesis that the socio-cultural evolution of humanity had reached an end point; that the final form of government had been found. It was his conviction that after the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, humanity had completed ideological evolution and the globalization of the liberal worldview had produced the final form of government. Only a few years after its publication, however, the liberal worldview was questioned from many quarters, including in the West.

The money thinkers

The MoneyMuseum commissioned Aldo Haesler, sociology professor at the University of Caen, to portray 50 money thinkers and briefly present their thoughts on money. Georg Simmel, Adam Smith and Max Weber were important milestones in the understanding of money. As interesting as the individual descriptions are, the texts do not condense into an overall view from which a theory of money would develop. New money books are launched almost weekly, which does not make it easy for the reader to keep track of them. In the following, I mention a few books that have impressed me personally.

Jim Simons is an American mathematician. He found the "code" of the financial market. He researched patterns, price patterns that form over and over again, and found some consistency. His Renaissance Corporation runs the Medallion Fund, but only for employees. Gregory Zuckerman's book "The man who solved the market" gives us a glimpse into Simon's secret world. His performance over the past 30 years is unparalleled. In the 1990s, only three years showed below 50% profit, there were no negative years. Since 2000 there was only one year below 50% profit (2003: +44%). Since 2010, the fund has been skimming well over US$5 billion per year. During all this time, the average annual increase in value was 66%, i.e. every 1.1 years the fund doubles, in four years it increases eightfold, and so on. Total trading profits during this period exceed US$100 billion. The code is guarded like the holy grail. This is not a win-win game, civil society does not benefit. Renaissance Corp. does not benefit society. Its profit is someone else's loss. Only the insiders can profit. One insider wanted to use his wealth to get involved politically, helped Trump get elected, became a big supporter of Bannon. He bought Cambridge Analytica, the company that used facebook data for political campaigns. The criticism reaped facebook, not the insider. Simons is revered in America, he has managed to do what so many others want to do.

Society of Anger, by Cornelia Koppetsch, 2019:

The remaining strata of the population are left with anger, or resentment, as it is called in the Odysee. Cornelia Koppetsch, a sociology professor, noticed more and more right-wing extremists in her environment. She got to the bottom of it and published her findings in "Gesellschaft des Zorns". A bestseller for many weeks. Claudia Koppetsch defines anger as resentment, fear, rage; as a state of mind AND a feeling that expresses itself on the political platform, as a political crisis. The non-privileged class no longer abides by political rules, but acts as taboo-breakers.

Politicians would now have to address the issues of the division of society, growth pressures, fears and sense of purpose, and migration, and are having a hard time doing so. Many people from the academic-cosmopolitan middle class believe that a liberal social order is the best possible of all worlds. This would be wantonly destroyed by the right-wing parties. The factual situation seems clear: liberalism is rational and logical; its right-wing populist challengers are irrational, if not insane; liberals tell the truth, right-wing populists spread lies; liberals stand for progress, right-wing populists want to restore the past; liberals are open-minded, freedom-loving, and egalitarian, while right-wing populists appear intolerant, authoritarian, and repressive. This narrative gives liberals the comforting feeling that they are on the right side of history. All this might still be viable if it were not simultaneously visible that the same milieus that advocate openness and tolerance are closing themselves off in exclusive enclaves of high-priced urban neighborhoods.

Globalization contains the paradox that it introduced radical class segregation across the globe, which contradicts the liberal worldview.

For its part, liberalism's idea of progress is undergoing rapid disintegration. It is becoming increasingly apparent that the imperial way of life, from which large majorities of the populations of the former colonial powers have long benefited, has reached its limits with globalization. Risks externalized to Third World countries are increasingly hitting back at their producers in the form of terror, financial crises and refugee flows.

Satoshi's Vision:

In 2008, the financial world changed drastically, not only because of the financial market crisis, but because of the publication "Bitcoin: A Peer to Peer Electronic Cash System". Much has happened in the decade that followed.

Aldo Haesler, Gelddenker

Aldo Haesler, Gelddenker

available in German only.

available in German only.

(book in translation)

(book in translation)

Eske Bockelmann

Eske Bockelmann

The money as a whole

Among the many money books with their details, there is, in my opinion, one work that has succeeded in providing an overall view of money. It reads like prose, that is, it is easy to read, but requires the dropping of prejudices for understanding. This riddle, described in more detail below, is worth exploring. It also contains the answers to our three questions posed in the introduction.

Since 2008, more and more people have become aware that all is not well with money and finances. Initially, people thought they could blame the banks, speculators and reckless entrepreneurs. But then came the realization that the "elites" might be to blame, or at least their inability to address this malaise. The elites stood for the regime money. This was not surprising, since the news about global warming, environmental crises, migration, division of society reached us daily. But the trend had been emerging for decades; the crises only sharpened the senses.

I am confronted with more and more groups who try to live money-free or with as little money as possible, which is a great challenge in our society. The effect on the psyche of these people always amazes me - they suddenly feel free and carefree. But most take the opposite approach: not an intense search for how to overcome money, but how to save it. Some initiatives were launched with enthusiasm, but rejected by the electorate. Again and again, ideas are put forward on how to protect money from further crises, how to safeguard it from greedy speculators, greedy banks and incompetent managers. It is not the system or the regime of money that is questioned, but its handling. Hence the attempt at reform.

In my opinion, this is an aberration. In a few years, people will be forced to question the regime of money.Money is a popular topic. Everyone knows exactly what money is all about, as long as it's about dealing with money. That you need it and what you need it for; how you get money, or at least how you could get money; what you can get for money and in what ways money can be used: None of this is a secret.

"Money makes the world go round" is a banal statement, but why do people refuse to question this system? Although environmental movements are calling for "Carry on like this is not an option! Turn or End!" and the concept of sustainability has entered the mainstream - modern society is defending its prosperity and lifestyle more resolutely than ever. It seems like a mystery or a taboo. How is it that we and our reality depend on money? How did money come to have this power?

I believe that global warming and its consequences such as floods, disintegration of entire areas and mass migration, but also the social division of society, the growth pressure of the economy, the general fear in society forces us to question the regime of money. In my opinion, this work by Eske Bockelmann offers for the first time an overall view of the phenomenon of money, its development and its characteristics. The book is worth reading.